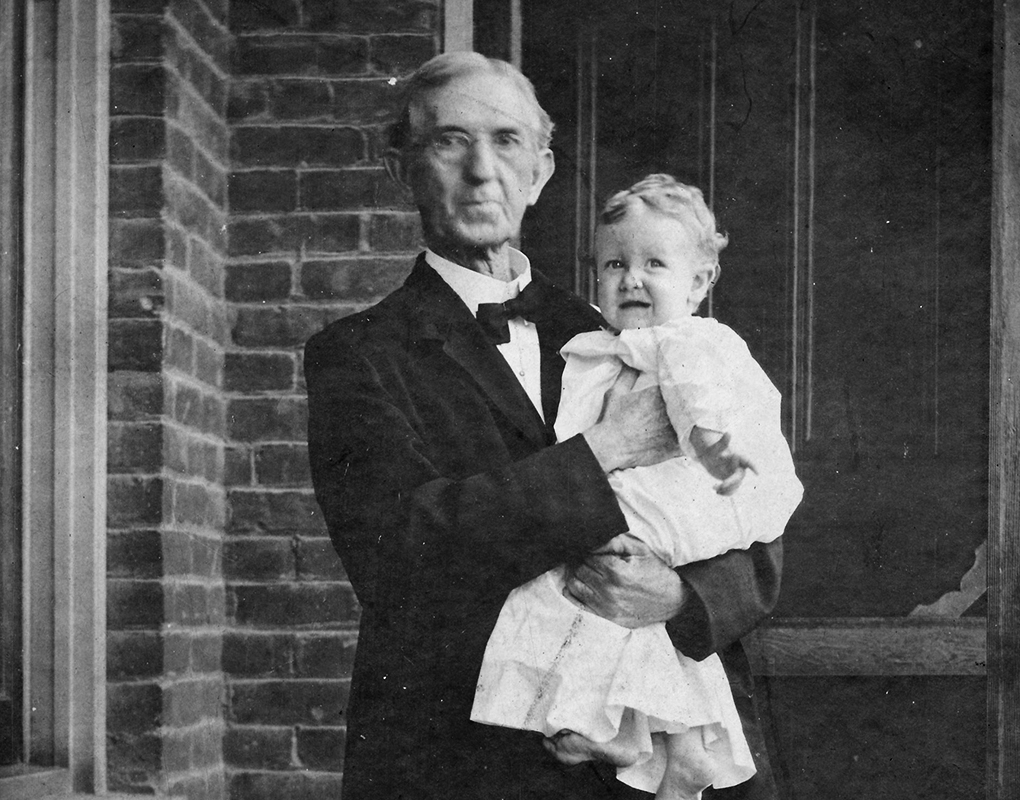

One of the most tumultuous chapters in the history of Southern Seminary was the presidency of William H. Whitsitt. In 1872, Whitsitt became the second professor hired by the founding faculty, and the seminary trustees elected him as the institution’s third president in 1895, following the death of John Broadus. Whitsitt was a cultured man of many gifts, and at the time of his election he held great respect among Southern Baptists as a church historian and denominational leader. However, his tenure as seminary president was beset with controversy, which culminated in his resignation and departure from the seminary in 1899.

The nature of the controversy surrounding Whitsitt centered upon his writings on the historical origins of Baptists, in which he claimed the baptismal practice of immersion had not existed between the apostolic age and the emergence of an organized Baptist denomination in England in the early 1640s. A large number of 19th century Southern Baptists rooted the rightness and distinctiveness of their religious identity in the belief that Baptist churches had existed in an unbroken line of succession since the apostolic era. Further complicating matters for Whitsitt was the fact that he had written some of his scholarly claims anonymously in non-Baptist publications, feeding into a public perception that Whitsitt was guilty of secrecy and deception. His removal from the seminary allowed some to perceive him as a martyr for academic free thought, but his private writings reveal a more troubling side of the seemingly soft-spoken scholar.

Whitsitt practiced the discipline of journaling extensively, but he often took the opportunity to record his frank, unflattering thoughts about his peers and acquaintances. As a young professor, Whitsitt respected his elder faculty members, but that did not spare them from being referred to in highly critical terms. Whitsitt held the teaching abilities of Basil Manly, Jr. in low regard, alleging that he “pretended to know Hebrew” and “he delights to have a finger in every pie; to attend to everything except his teaching.” ((James H. Slatton, W. H. Whitsitt: The Man and the Controversy (Macon: Mercer University Press, 2009), 121.)) The root of Whitsitt’s frustration with James P. Boyce likely owed to his dissatisfaction with his salary relative to older professors, and in his diary he referred to him as “a dunderhead” and “a very uninteresting person . . . without any kind of importance.” ((Ibid., 84, 117. )) A failed marriage proposal to Boyce’s daughter Elizabeth only added to the sense of enmity between the men, as Whitsitt admitted his own pride left Miss Boyce “in her single misery.” ((Ibid., 86.))

Though fraternally closer to Broadus throughout life, Whitsitt suspected his mentor of colluding to entrap him in heterodox charges concerning his view of biblical inspiration on the heels of C. H. Toy’s resignation for the same matter. His diary suggests this notion compelled Whitsitt to limit his associations with his older peers: “I keep to my side of the house and allow Boyce and Broadus to keep to their side of the house. . . . I desire to cultivate no other relations with them.” ((Ibid., 84.)) Curiously, Whitsitt even recorded unflattering remarks about Broadus’s walk, noting his “ungainly figure.” ((Ibid., 122.))

Whitsitt also soured in his estimation of his own pastor T. T. Eaton, whom he came to view as too rigid in his denominational fervor. Despite a lifetime of shared experiences and common labor on behalf of Baptist causes, in 1895 Whitsitt privately wrote that God should take the life of Eaton immediately: “His usefulness is about over. . . it would be a mercy of the Lord for him to die now.” ((Ibid., 174-75.)) Eaton lived until 1907, but the men’s relationship turned into one of antagonism and distrust, exacerbated by the controversy over Baptist origins and its fallout. ((See especially their correspondence exchanged in September, 1900, in the T. T. Eaton Papers, SBTS Archives.))

The harsh private thoughts of Whitsitt recorded in his diary give the appearance of a man who harbored uncharitable resentment toward his fellow workers. Despite the fact that Whitsitt would often speak highly of the same people in public, his private opinions might also suggest a degree of hypocrisy which even he might not have been fully aware. Whatever legitimate grievances Whitsitt might have had with his co-laborers, the recorded evidence suggests he hardly handled those criticisms constructively. History cannot positively instruct subsequent generations how Whitsitt’s life (and the history of the seminary) might have played out differently if he had pursued reconciliation and the mending of relationships damaged by misgivings, whether perceived or real, through mutual forgiveness.

A large collection of Whitsitt’s manuscripts and personal library are available for research in the Archives office in the James P. Boyce Centennial Library.

FOOTNOTES