“Open your Bibles, your phones, or your tablets with me to the passage for today’s sermon.” This now common refrain in pulpits across America represents the seismic shift the past decade of the digital revolution has created in the lives of nearly 200 million people. And it’s not just in this country — in four years, 70 percent of the world’s population will be equipped with smartphones.

But what effects do these technologies have on the human experience in the 21st century? And how do these challenges factor into the spiritual devotion of millions of Christians?

At every waking moment, we are connected to our devices — a world of infinite possibilities is at our fingertips. But more and more, studies are showing just how disconnected we are from each other.

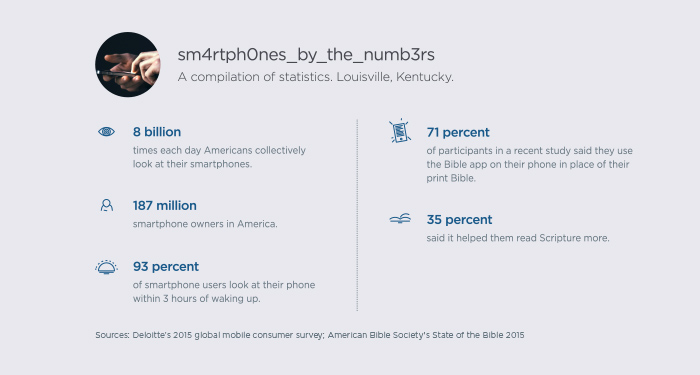

A recent survey suggests American smartphone users collectively check their devices upwards of 8 billion times per day. But most Americans are unaware just how often they contribute to this trend — according to a recent Gallup survey 61 percent of respondents said they look at their smartphones “a little less often” or “a lot less often” than other people they knew.

In addition to feeling more connected, we’re also multitasking. Statistics show Americans use their smartphones while engaged in other activities — 89 percent said they use them during leisure activities, 87 percent while talking to family and friends, and 87 percent while watching TV. The frequency of multitasking has given rise to a distracted age. Whether you realize it or not, your smartphones, tablets, and streaming devices could be robbing your spiritual life of empathy, solitude, and focus.

THE LOSS OF EMPATHY

Since the advent of the digital revolution, psychologist Sherry Turkle has been keeping tabs on the effects these technological trends have had on human behavior. A professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Turkle has recently written Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Ourselves (2011) and Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age (2015). These works describe how Americans now find it uncomfortable to be alone without digital distraction, and how an increasing number of young people are avoiding face-to-face conversations and even voice calls because human interaction is “messy.”

“Digital connections and the sociable robot may offer the illusion of companionship without the demands of friendship,” Turkle writes in Alone Together. “Our networked life allows us to hide from each other, even as we are tethered to each other. We’d rather text than talk.”

Based on decades of research, Turkle says digital devices “allow us to ‘dial down’ human contact” and appear to offer “more control over human relationships.” Americans increasingly avoid face-to-face conversation and the sound of the human voice to protect emotional vulnerability and maintain the paradox of “being in touch with a lot of people whom they also keep at bay.”

Most alarmingly, Turkle’s research has recently arrived at the conclusion that “digital natives” — a term used for anyone raised in a technology saturated culture — are losing the capacity for empathy. Turkle cites her study showing a 40 percent decline in empathy among college students over the past 20 years. As young people lose solitude, they also lose the reward of learning to appreciate difference and diversity in other human beings.

Do not dismiss Turkle’s warnings as nostalgic for the “good ole days.” She does teach at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Rather than rejecting smart devices, Turkle says recognizing what we’re missing in the digital age prepares us “to shape it in ways that honor what we hold dear.”

These trends are particularly troubling for T. David Gordon, professor of religion and Greek at Grove City College. Gordon also studies media ecology — a field which studies the effects of technology on the human experience — and his book Why Johnny Can’t Preach assesses how the rise of digital media has shaped contemporary preaching. He says the loss of empathy is “catastrophic” for Christians who hold dear the image of God in human beings and the human nature of Jesus Christ.

“For humans to be human, they have to be empathetic and especially to be ambassadors for Christ, who incarnated,” Gordon said in an interview with Towers. “Talk about empathy; nothing’s more empathetic than the incarnation. For us to be uncomfortable with an incarnate human, and to say that they’re ‘messy,’ what does that do to our doctrine of Christ?”

Gordon says one result of smartphones and instant messaging is that digital natives are able to read literally through their devices, but no longer able to pick up body language from their human conversation partners. He warns not being able to “read people” will make many digital natives who are training for the ministry “ineffective” as pastors and “terrible” as spouses unless they learn to engage in face-to-face conversation. To rectify this, Gordon suggests using smartphones to arrange face-to-face human interaction, not to substitute it with instant messaging.

THE DISAPPEARANCE OF SOLITUDE

Imagine with me for a second the scene in 1 Kings 19, when the Prophet Elijah flees to the mountain of Horeb. A great wind, an earthquake, and fire appear before Elijah, but he finds that the Lord comes to him in a whisper: “What are you doing here, Elijah?”

In our digital age of distraction, do we risk missing the whisper?

Turkle and other media ecologists have scientifically established how smartphones can diminish our human contact. It should be natural for us to at least consider how they may affect our relationship with God.

Because technology is “always on” and “our machine dream is to be never alone,” as Turkle writes, solitude and separation from our devices can be an awkward experience and even cause anxiety.

“The Scriptures commend meditation on God’s Word and reflecting on truths, which require a certain affinity for solitude,” Gordon said. “If the digital world trains people to find solitude itself off-putting, then they can’t have much quality time with God.”

THE LACK OF FOCUS

This quality time with God begins with regular Bible reading. In the past five years, reading the Bible primarily on smartphones and tablets has skyrocketed with the success of apps like YouVersion, which currently boasts more than 215 million downloads. Half of all Bible readers use YouVersion or a similar app at least occasionally.

Gordon says this trend can be problematic depending on individual habits. If a smartphone user spends a large amount of time on social media, addictive games like Candy Crush, or watching videos, they can carry over an “associative meaning” to other, more substantial apps stored on the device, like the eternal, inspired Word of God.

“I think associative meaning is real psychologically,” Gordon said. “I don’t know how we mentally transition from using our devices to play games or watch YouTube videos and then we pop over to a biblical app.”

Is it possible to make your screen a sacred space? We asked Donald S. Whitney, professor of biblical spirituality at Southern Seminary, who has written influential books on spiritual disciplines, most recently Praying the Bible. Despite his love for fountain pens, Whitney reads the Bible and stores his journals on his iPad, and takes prayer walks with his smartphone open to the Psalms.

When Whitney uses his device, he makes sure all his notifications are turned off so he can remain distraction-free. He notes that, while smart devices make the Bible more portable, they also can bring along distractions.

“It always comes back to discipline,” said Whitney, who recommends a “technology fast” for those feeling their devices have a strong pull on their heart. “Technology is a double-edged sword. It makes it more convenient — you always have your Bible with you, you can have devotional time anywhere and anytime — but there’s a corresponding downside with distractions.”

That doesn’t mean, however, we should resist any and all technology, Whitney said, referring to Ecclesiastes 7:10: “Do not say, ‘Why were the old days better than these?’ For it is not wise to ask such questions.” Rather, we should seek to live as godly, Bible-centered Christians in the technology-saturated culture in which God has placed us, Whitney said.

This same tension is apparent even in the publishers who create Bible products. Bobby Gruenewald, the founder of YouVersion and Life.Church innovation leader, said, “We believe God’s Word is powerful and able to transform lives, and we’ve built the Bible App to help people engage with Scripture frequently.”

“On the surface it may appear that these features are about convenience, but what they really represent is people choosing to use the device they always have with them to create touchpoints throughout their day to reconnect with God through his Word,” Gruenewald said in an email to Towers. “Many people have shared that engaging with the Bible through the app has been a catalyst for spiritual transformation in their life: relationships with Christ are beginning, marriages are being restored, families are being strengthened and reunited, and faith is being renewed around the world.”

But one of the most surprising trends in the past few years is Crossway’s counter-revolution of publishing innovative print Bibles. The leading evangelical publisher of the English Standard Version has released a variety of Reader’s editions — Bibles without any verse numbers or headings — and Journaling Bibles. One of the most recent Journaling Bibles is an Interleaved Edition with blank pages for lengthier notes and reflection, modeled after colonial American preacher Jonathan Edwards’ personal Bible.

Dane Ortlund, executive vice president of Bible publishing and Bible publisher at Crossway, said that while the company makes “smooth digital interaction with the Bible a significant priority,” he believes “digital reading should complement, not displace, print reading.”

“This is especially the case with the Bible, which requires thoughtful, unhurried, distraction-free reading,” Ortlund said in an email to Towers. “Most of us are well aware of the experience of trying to read something on a phone or tablet only to be repeatedly interrupted by incoming text messages or emails. Even if not, there remain a million interesting websites — along with Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and all the rest — to clamor for our attention.”

While the answer to the clamoring is personal discipline, the solution begins with awareness — recognizing that, while our devices may connect us with a brave new world, we may find ourselves disconnected from divine communion.

“When you sit down with a print Bible, with all your devices turned off, you stand a chance of hearing from God more than from your friends,” Ortlund said. “You are stepping in out of the storm.”