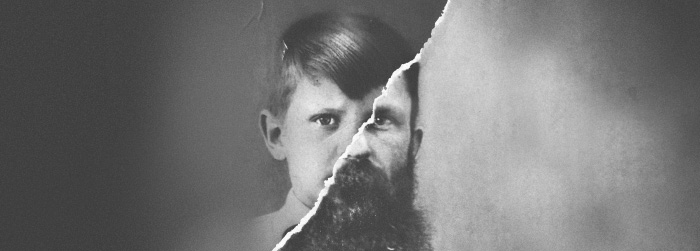

When the fifth professor elected to the faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary signed the Abstract of Principles, his pastor, mentor, and colleague John Broadus proclaimed he was “our shining pearl of learning — not an ordinary star, but a brilliant meteor.” Founding President James Petigru Boyce soon regarded his former student “easily best” in scholarship among the professors. But 10 years later, Crawford Howell Toy resigned amid a denominational controversy over his views of biblical inspiration, an event which branded him a heretic. And, by the end of his life, he had abandoned the Christian faith.

Toy’s fate entered Southern Seminary lore and later became a cautionary tale for the conservative resurgence in the Southern Baptist Convention. Legendary SBC pastor and Southern alumnus W.A. Criswell popularized the story in his famous 1985 sermon “Whether We Live or Die,” reclaiming the narrative from moderates who viewed Toy as a martyr for academic and intellectual freedom. To this day, SBTS President R. Albert Mohler Jr. begins each ceremonial signing of the Abstract of Principles with a grave reminder of Toy’s heresy. But the full story of his time at Southern, recounting his meteoric rise from star student to the school’s most popular professor, makes his eventual departure from the faith even more tragic and raises questions about the value of placing eternal confidence in academic success.

An important note from the outset: Unlike the Netflix documentary Making a Murderer, our goal is not to victimize the fifth professor to sign the seminary’s confessional document; he is responsible for his own heretical theological trajectory. Toy was unquestionably a man of supreme intelligence and appeared to be very pious, but taking an honest look at his life and legacy is more sobering than a brief morality tale, demonstrating the difference between academic achievement and spiritual maturity. Toy illustrates that excellence in theological studies must be accompanied by true virtue.

‘An uncommonly conscientious and devoted man’

Toy was among the original class of students when Southern Seminary opened its first session October 1859 in Greenville, South Carolina. He enrolled so he could prepare for service with the Foreign Mission Board of the SBC (now known as the International Mission Board) because he believed “all young ministers ought to become missionaries to the heathen unless they could show good reason to the contrary.”

Toy first met John Albert Broadus when he enrolled at the University of Virginia, where Broadus was assistant professor of ancient languages. Toy regarded him as “an admirable Greek scholar” and attended the Broadus-led Charlottesville Baptist Church.

Toy demonstrated a remarkable knack for languages in college, taking Latin, Greek, Italian, and German. He no doubt inherited this ability from his father, Thomas, who owned a successful drugstore and developed a proficiency in seven languages.

A year before his conversion, Crawford Toy encountered the issue of biblical inspiration in his studies at UVA, as in one letter he recounts philosopher David Hume’s “attempts to prove the probable falsity of the New Testament narratives.” Toy may not have questioned the inspiration of the Bible at this time, and in 1854 he was converted and baptized by Broadus. Four years later, Toy joined a group from his home church in Virginia to protest, unsuccessfully, the new seminary’s hiring of their pastor.

Soon after graduating from college he began teaching at the Albemarle Female Institute, where one later admirer would note his classroom demeanor was “so extremely dignified and exquisite that the girls stand in awe of him.” One of his first students was the brilliant skeptic Charlotte Moon, whose friends called her “Lottie.”

During a spring 1859 revival meeting, which Broadus led at the school, Lottie Moon professed faith in Christ and was baptized. As she continued her education at Albemarle, Moon determined to serve on the mission field. When Toy, who had developed a relationship with her beyond that of a teacher, asked to marry her in 1861, Moon rejected his proposal because of her commitment to go overseas. But Toy’s friendship with Moon would continue through letter writing for nearly 20 years and finally end in painful circumstances.

At Southern, Toy’s missionary zeal and intellectual aptitude instantly impressed his professors and he shot up to the top of the class by completing three-fourths of the curriculum in the first year. He was elected president in 1859 of the Andrew Fuller Society, a debate club named after the seminal Baptist theologian. During the Christmas holidays, when students were not able to return home, Toy launched a student prayer group.

Reporting on the progress of the seminary in its first year, Broadus remarked that Toy “is among the foremost scholars I have ever known of his years, and an uncommonly conscientious and devoted man.” Had seminary awards been a practice as they are now, Toy would certainly have won his share.

In June 1860, Toy appeared before the Foreign Mission Board and was appointed to serve in Japan. Later that month, Broadus and several other pastors ordained Toy to the gospel ministry.

The Civil War interrupted the Board’s plans to send Toy to Japan, a decision which Toy nearly protested by going without support. Instead, Toy enlisted in the Confederacy, serving first as a private in the artillery and then as a chaplain in General Robert E. Lee’s army. During the war, observers said Toy occupied his time studying languages, carrying his Hebrew Bible and dictionary and also reading German “for amusement.”

After the war, Toy wanted to study in Europe, and in 1866 he set sail for Germany and possibly away from orthodoxy.

Champion of orthodoxy? The seeds of Toy’s heresy

Historians have sometimes pointed out the apparent irony that Toy resigned over the issue of inspiration when he began his teaching career as a champion of orthodoxy. But even before he left to study at the University of Berlin, Toy expressed in religious newspapers a troubling admiration for Virginia worship services that he said demonstrated the “spirit of the Lord” despite being doctrinally unsound.

Toy’s separation of spiritual intent and doctrinal integrity parallels his biblical hermeneutic of distinguishing between the inner and outer meanings of Scripture. This also foreshadows his eventual adherence to religious pragmatism — a theistic belief that truth is what “we are constantly creating for ourselves.”

After returning to the United States in 1868, Toy briefly accepted a teaching position at Greenville’s Furman University before being elected to the faculty of Southern Seminary. In a meeting with the founding faculty, Boyce and Broadus decided Toy should give the inaugural address to the 1869 academic year.

His ensuing address, “The Claims of Biblical Interpretation on Baptists,” made a resounding impression throughout higher education. At the dawn of its second decade, Southern Seminary had a rising star and was on the cusp of academic respectability.

Toy’s conclusions in this lengthy address fit within the confessional document he signed that year, specifically the statement on Scripture in the Abstract of Principles: “The Scriptures of the Old and New Testament were given by inspiration of God, and are the only sufficient, certain and authoritative rule of all saving knowledge, faith and obedience.”

In fact, Toy’s emphasis on the special responsibility on Baptists for studying Scripture echoes the confessional statement, as he describes “our complete dependence on the Bible.”

“We profess to make it, and it alone, our religion,” Toy said. “We accept all that it teaches, and nothing else. In doctrine and practice, in ordinances and polity, we look to it alone for instruction, and no wisdom or learning of men avails with us one iota, except as according with the inspired Record. … It is our pole star.”

Yet even Toy’s inaugural address hints at a theological trajectory that would quickly cause him to drift from a conviction in the Bible’s inspiration. Southern Seminary’s Gregory A. Wills, who wrote the sesquicentennial history of the school, describes Toy’s hermeneutic as a Nestorian division of the spiritual and literal meanings of Scripture (Nestorianism is a fifth-century heresy emphasizing the disunity of Christ’s divine and human natures).

In his address, Toy encouraged seminary students “to lay hold of the Word of God, on its divine and on its human side, in its intellectual and in its spiritual elements.” One of the methods for doing this is to accept scientific discoveries, “furthering the understanding of the Bible.” Although he expressed neutrality on Darwinism at the time, Toy said further research in this evolutionary theory “will produce valuable results, and will illustrate rather than denude the Scriptures.” Take for, instance, this troubling remark which gives more evidence to Toy’s spiritual-literal dichotomy:

Very slowly the Christian mind has come to the conclusion that the Bible is not a teacher of science — that such a character would interfere with the intellectual development of the race, or would make its language, which would necessarily in that case be conformed to perfect science, unintelligible up to the moment of the culmination of man’s studies — that it rather conforms its language to that phenomenal observation which will probably last to the end of time, as demanded of a book intended for all time — that its standpoint is not that of science, and the emphasis which it puts on things not a scientific one, since it uses all the array of worldly facts and experiences simply as framework for the scheme of redemption.

Subsequent to his address, the Virginia Baptist newspaper The Religious Herald praised Toy for his “eminent lingual attainments, his sound judgment, amiable manners, and earnest piety” and concluded that he would one day “rank among the foremost biblical scholars of the world.”

‘I would give my right arm’

Ten years later, Toy stood at the Louisville train station with his beloved mentors Boyce and Broadus. The seminary’s trustees had regretfully accepted Toy’s resignation at the Southern Baptist Convention annual meeting in Atlanta, and now he was set to part, though not “part to meet.”

In his memoir of Boyce, Broadus describes the now-legendary moment before the train’s arrival:

Throwing his left arm around Toy’s neck, Dr. Boyce lifted the right arm before him, and said, in a passion of grief, “Oh, Toy, I would freely give that arm to be cut off if you could be where you were five years ago, and stay there.”

Yet five years before, Toy had already adopted the Darwinian theory of evolution and began revising his interpretation of Old Testament history.

Even as a young boy, Toy was reportedly fascinated with theories of human origin. His biographers note the adult Toy was not pleased harmonizing the Old Testament with modern geology, astronomy, and ethnology, and he was “profoundly interested” in Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species, which coincidentally appeared in print in 1859, the year Southern Seminary opened.

Though he indicated neutrality to Darwinism in his 1869 address, Toy told his students five years later Christianity and evolution were compatible and he delivered a popular lecture in Greenville promoting human evolution prior to the seminary’s relocation to Louisville in 1877.

By divorcing the Bible’s divine and human aspects, Toy embraced higher criticism and followed in the footsteps of his German teacher Isaak Dorner, who also distinguished between Scripture’s true inward meaning and its fallible outward form. Toy also began teaching an evolutionary reconstruction of Israel’s history, reordering the Old Testament books so as to dismiss the Pentateuch’s historical value.

What caught Boyce’s attention in 1877 was a student’s complaint to the president that Toy “taught the writer of the 16th Psalm had no reference to the resurrection of Jesus.” At this point, Toy denied all the traditional messianic prophecies, arguing instead that Christ fulfilled general spiritual yearnings.

Boyce wrote to Toy the following spring, asking him to refrain from theoretical speculation and to instruct students in “history as it stands.” Broadus also labored privately with Toy to restore him from these theological errors, which Wills says indicates Broadus “believed that Toy was right in heart and right in fundamental principles.”

“There’s a nobility in Broadus’ hopefulness, but there’s a wonderful integrity to Boyce’s sound judgment with regard to character and how it will play out,” said Wills, dean of Southern’s School of Theology and professor of church history, in an interview.

Around 1877, Toy’s views began circulating beyond the seminary campus and into the churches of the Southern Baptist Convention. As the most popular professor, Toy taught more students than any of his colleagues and his students continually asked Toy about his evolutionary views, which he saw as beneficial for “truth and piety” despite Boyce’s protest. Soon, his disciples began taking pastorates and teaching posts, where they promoted this new approach to the Bible.

In December 1878, Toy’s heresy became a denominational controversy. An anonymous writer known as E.T.R. — later revealed as Josephine Eaton — wrote to The Religious Herald, “At least two Professors in Baptist theological institutes are far from being sound in doctrine. One does not believe in the inspiration of Moses, nor, indeed, of various other parts of Scripture. … The other Professor is a Universalist.”

While Broadus considered Eaton’s letter “imprudent and foolish,” he and Boyce both felt it was in the best interests of the seminary and the denomination for the trustees to investigate and determine Toy’s fate.

The decision no doubt became easier for the trustees when Toy published a controversial Sunday School lesson in 1879. Though he had already written some of his liberal insights for the Sunday School Times, his lesson published that April on “The Suffering Servant” in Isaiah 53:1-12 branded him a heretic in the denomination. In this article, Toy insisted “The Suffering Servant,” traditionally considered a messianic prophecy, referred only to the nation of Israel and had only a general and indirect fulfillment in Christ.

Less than a month later, Toy appeared before the trustees with a resignation letter defending his views against inspiration and hoping the board would vindicate him of any wrongdoing. In the letter, Toy stated “discrepancies and inaccuracies” in the Bible do not “invalidate the documents as historical records.”

“I am slow to admit discrepancies or inaccuracies, but if they show themselves I refer them to the human conditions of the writers, believing that his merely intellectual status, the mere amount of information possessed by him, does not affect his spiritual truth,” Toy wrote.

After deliberating, the trustees unanimously accepted Toy’s resignation May 7, 1879, although many Southern Baptists and former students disagreed. Writing to his wife the week of Toy’s resignation, Broadus wrote:

Alas! the mournful deed is done. Toy’s resignation is accepted. He is no longer professor in the Seminary. I learn that the Board were all in tears as they voted, but no one voted against it. I cannot yet say who will be elected in his place. … We have lost our jewel of learning, our beloved and noble brother, the pride of the Seminary.

In a 1997 Founders’ Day address on Toy’s hermeneutics, former Southern Seminary professor Paul House said, “Boyce and Broadus’ reaction to Toy’s leaving the faculty illustrates the fact that one should never rejoice in the departure of an individual from the seminary family due to theological reasons. We should, instead, feel as Boyce did, that we would rather lose an arm than the fellowship of a brother or sister in Christ.”

‘American heretic’

‘American heretic’

In reflecting on this painful chapter, Broadus said Toy “thought strange of the prediction made in conversation that within 20 years he would utterly discard all belief in the supernatural as an element of Scripture.” The prediction came true within a decade.

Shortly after his dismissal from Southern, Toy was set to marry Lottie Moon. The couple had resumed correspondence after the missionary wrote home of her loneliness on the mission field. But in 1880, Moon called off the wedding, citing her disagreement with Toy’s theological evolution. She never married and died 32 years later on Christmas Eve 1912. Southern Baptists would later name their annual Christmas offering for international missions after Moon.

Toy remained somewhat of an academic celebrity because of his public dismissal from the seminary, and after rejecting the presidency of Furman, Toy was appointed Hancock Professor of Hebrew and Oriental Languages at Harvard University in September 1880.

Harvard President Charles William Eliot, writing to the other candidate for the position, said Toy was an “American heretic, whose views on Isaiah had offended the Baptist communion to which he belonged.”

Toy left a lasting legacy at Harvard, which had only offered Hebrew before 1880, by introducing more Semitic languages — Aramaic, Arabic, and Ethiopic. While his theological views had changed, his Harvard colleagues praised Toy for his “courage, both physical and moral, his imperturbable poise, his complete freedom from self-seeking, his catholicity of spirit, his geniality of speech and manner, his quiet and inoffensive humor.”

After eight years at Harvard, Toy withdrew his membership from the Old Cambridge Baptist Church. In 1890, he published Judaism and Christianity, in which he denied the divinity of Christ in the New Testament. By 1907, Toy was an avowed pragmatist, rejecting absolute religious truth.

Toy eventually acknowledged the necessity of his departure from the seminary. He continued his correspondence with Broadus, who recommended his hire to Harvard, and wrote to his mentor after the publication of the Memoir of James P. Boyce, “You are quite right in describing my withdrawal as a necessary result of important differences of opinion. Such separations are sometimes inevitable, but they need not interfere with general friendly cooperation.”

He and his wife, Nancy, whom he married in 1884, enjoyed a relatively happy life at Harvard, joining the higher class of society where they became lifelong friends with Woodrow Wilson, later to become the 28th president of the United States.

Contrary to some legends, Toy was not a bitter man in old age, although he was blind and disabled for nearly two years before his death May 12, 1919 at 83.

Postscript: How to avoid Toy’s heresy

For many who read this retelling of Toy’s tragic drift from the faith, they may be troubled to find similarities with their own seminary or spiritual experiences. What then do seminary students and, even professors, make of someone who was once considered a remarkable man of faith by his mentors and peers?

“Neither our piety nor our success in studies are grounds of faith,” said Wills in an interview with Towers on Toy’s legacy. “We must humble ourselves and humble these things and pray for God’s mercy to keep us from error, pride, idolatry, and an unbelieving heart. And ultimately that’s it for Toy: the evidence of his eyes and reason caused him not to trust the assertions of Scripture.”

Toy, Wills said, is an “object lesson” in understanding Matthew 7:21-23, when Jesus says, “Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven. … On that day many will say to me, ‘Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name, and cast out demons in your name, and do many mighty works in your name?’”

According to Wills, Toy demonstrates a religious affection “analogous to the affection the true saints experience” such that he was able to apprehend the things of God and appeared to be “the real thing.”

But Toy also illustrates the “heartbreaking” nature of heresy and the folly of seeking academic credibility at the expense of confessional identity, says Matthew J. Hall, vice president for academic services and assistant professor of church history.

Regarding Toy as a martyr for academic freedom and intellectual inquiry, as the moderate Baptists did in the 20th century, is a “tragic way of remembering Crawford Toy,” Hall said. “Toy reminds us that it’s very painful when people you know and love renounce the faith.”

Toy’s life and legacy provides a warning for seminary students today, but his clear example of error actually provides a helpful framework for how not to be the next Crawford Howell Toy:

- Submit to the inspiration and authority of Scripture, both its historical and spiritual claims.

We would do well to heed Toy’s own remarks about Scripture in his inaugural address: “Accept all that it teaches, and nothing else.” The inspired Word of God is the believer’s only guide for instruction and wisdom, and its historical truthfulness is intertwined with its spiritual reality. Abandoning the historical claims of Scripture while trying to maintain inward truth will logically result in denying the divinity of Jesus. - Evaluate your faith and spiritual fruit, not just your seminary GPA or academic credentials.

Whether we admit it or not, seminary students can be tempted to focus solely on completing coursework and justifying it as spiritual devotion. Earning an A in Personal Spiritual Disciplines is not a substitute for a healthy private prayer life. - Do not elevate spiritual intent above doctrinal integrity.

After he graduated from seminary, Toy caused a small stir by commending heterodox worship services in the Baptist newspaper for their spiritual devotion, foreshadowing his adherence to pragmatism. Praying several times a day or reading the Bible through in a year is futile if not marked by virtuous love for Christ and belief in essential doctrines.