In 1879, Crawford H. Toy resigned his position as Southern Seminary’s professor of Old Testament due to conflict between his views on biblical inspiration and the institution’s confessional statement, the Abstract of Principles. Toy’s departure — necessary to preserve the school’s doctrinal integrity and uphold the trust of the Southern Baptist Convention — left a great void of scholarship that the remaining seminary faculty was anxious to fill. In 1883, the seminary found its man, a young professor named George W. Riggan.

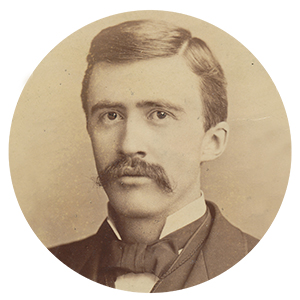

A native of Virginia named in honor of George Washington, Riggan professed faith in Christ as a teenager and pursued the Baptist ministry after abandoning a potential career as a boatman. Having graduated from Richmond College with high honors, he enrolled at Southern Seminary eager to apply himself to both dutiful scholarship and frequent preaching opportunities. Even John A. Broadus, widely regarded as one of the finest preachers of his day, remarked that Riggan “spent too much time in preaching … and during the second session he was sometimes taken ill, and he simply replied that he was sure it was his duty.”

Riggan’s rigorousness earned him a position as an assistant instructor in Hebrew, Greek, and homiletics even before his graduation from the seminary. In addition to his academic work, he served as a commuting pastor of the historic Forks of Elkhorn Baptist Church of Woodford County, Kentucky. Distinguishing himself as the antithesis of Crawford Toy, Riggan authored multiple articles published in Baptist newspapers that defended the infallibility of Scripture and the trustworthiness of the biblical canon. In his 1883 article titled “What Is the Proper Attitude towards Recent Biblical Criticism,” Riggan cautioned against uncritical acceptance of the claims of grammatical-historical critics that undermined the authority of Scripture.

This theme also characterized his faculty inaugural address, which he titled “The Preacher’s Adaptation to His Intellectual Environment,” delivered Oct. 1, 1883. Fittingly enough (considering the Darwinian naturalism which had adversely influenced Toy’s theology), Riggan’s address opened with an acknowledgment of the predominance of the “survival of the fittest” lifecycle in the natural world, observing how adaptation to environment is an essential component of nature. He proposed that a preacher should likewise adapt himself to his intellectual environment, defined as “the intellectual influences which distinguish his time and country from other times and countries.”

Riggan emphasized this intellectual adaptation must never be an accommodation to the unbiblical conclusions of modern thought, because “as the messenger of God must not slavishly imitate or affect the tastes of his community … so in intellectual matters he must not be a mouthpiece for this time.” The Christian preacher must be wise in applying the truths of Scripture to the problems of his own day. Riggan’s call to adaptation meant a preacher must cultivate “close intellectual sympathy with his hearers … for the preacher’s power as a man, apart from the authority of his message and the Spirit’s presence, is the power of sympathy.” Furthermore, the preacher’s adaptation would enable him to appreciate the positive contributions of modern thought while granting him “a knowledge of the best points of attack.” A well-informed argument makes a strong case for truth, rather than simply pontificate complaints at the world’s many problems.

Riggan encouraged busy pastors to make greater strides to understand the ultimate roots of cultural thought in ways that went beyond newspaper headlines or mundane conversations. At the same time, he warned the eager preacher against becoming seduced by modern thought to such an extent as to “talk with more zest about science and art than about personal religion.”

Less than two years later, Riggan died suddenly on April 18, 1885, after being stricken with meningitis at the age of 30. John A. Broadus delivered his funeral sermon, which was later published in his Sermons and Addresses (1886), and remarked highly of Riggan’s acute intellect, high personal character, commitment to doctrinal orthodoxy, and unbridled enthusiasm for Christian service: “While fully in sympathy with the spirit of progress, and eagerly examining all living questions, Dr. Riggan was unwaveringly convinced of the truth of those opinions which are established among Baptists concerning the authority of Scripture and the Theology which Scripture exhibits.”

Like the thrill of a well-orchestrated fireworks display, Riggan’s lifespan was brief yet memorable. Had his health endured, he would likely have become one of the seminary’s most accomplished and respected professors. The full text of his inaugural address can be downloaded from the Boyce Digital Library: http://digital.library.sbts.edu/handle/10392/4929.

John A. Broadus, Sermons & Addresses (Baltimore: H. M. Wharton & Company, 1886), 354-55.

George W. Riggan, “What Is the Proper Attitude towards Recent Biblical Criticism,” Religious Herald, January 18, 1883. Gregory A. Wills, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1859-2009 (Oxford University Press, 2009), 59.

Riggan, “The Preacher’s Adaptation to His Intellectual Environment: Inaugural Address” (Louisville: Hull & Brothers, 1883), 7.

Broadus, Sermons & Addresses, 360.