Andrew Fuller was an indefatigable and fearless Baptist theologian and minister, an outstanding figure with qualities that make him one of the most attractive figures in Baptist history. Michael A.G. Haykin, professor of church history and biblical spirituality and director of the Andrew Fuller Center for Baptist Studies at Southern Seminary, provides a summary of his life and impact in honor of the bicentennial of his death.

Andrew Fuller was born on Feb. 6, 1754, at Wicken, Cambridgeshire. His parents, Robert Fuller and Philippa Gunton, rented and worked a succession of dairy farms. When Fuller was 7 years old, his parents moved to the village of Soham and joined a Particular Baptist work in the village. John Eve was the pastor of this small church as well as a hyper-Calvinist — that is, according to Fuller, one who “had little or nothing to say to the unconverted.” The sovereignty of God in salvation was so prominent a theme in English hyper-Calvinist circles that it seriously hampered effective evangelism.

Nevertheless, in the late 1760s, Fuller began to experience strong conviction of sin, which issued in his conversion in November 1769. He was baptized in April 1770 and joined the Soham church. Over the course of the next few years, it became very evident to the church that Fuller possessed definite ministerial gifts. Eve left the church in 1771 for another pastorate. Fuller, who was self-taught in theology and who had been preaching in the church for a couple of years, was formally inducted as pastor on May 3, 1775. The church consisted of 47 members and worshiped in a rented barn.

‘THE GOSPEL WORTHY OF ALL ACCEPTATION’ AND ITS IMPACT

Fuller’s pastorate at Soham, which lasted until 1782 when he moved to pastor the Baptist church in Kettering, Northamptonshire, was a decisive period for the shaping of his theological outlook. It was during these seven years that he began a lifelong study of the works of Jonathan Edwards, his chief theological mentor after Scripture. Then, it was during his pastorate at Soham that Fuller decisively rejected hyper-Calvinism and drew up a defense of his own theological position in The Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation, though the first edition of this book was not published until 1785.

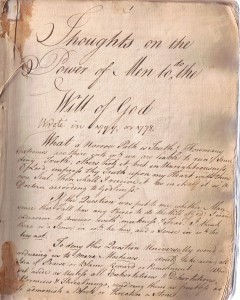

A preliminary draft of The Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation was written by 1778 (this first draft is in the Archives of Boyce Centennial Library). Two editions of the work were published in Fuller’s lifetime. A first edition was published in 1785. The second edition, which appeared in 1801, was subtitled “The Duty of Sinners to Believe in Jesus Christ,” which expressed the overall theme of the book. There were substantial differences between the first and the second editions, but the work’s major theme remained unaltered: “faith in Christ is the duty of all men who hear, or have opportunity to hear, the gospel.” This epoch-making book sought to be faithful to the central emphases of historic Calvinism while at the same time attempting to leave preachers with no alternative but to drive home to their hearers the universal obligations of repentance and faith.

With regard to Fuller’s own ministry, the book was a key factor in determining the shape of that ministry in the years to come. For instance, it led directly to Fuller’s wholehearted involvement in the formation of the Baptist Missionary Society in October 1792 and the subsequent sending of the society’s most famous missionary, William Carey, to India in 1793. Fuller also served as secretary of this society until his death in 1815. The work of the mission consumed an enormous amount of Fuller’s time as he regularly toured the country, representing the mission and raising funds.

Fuller’s commitment to the Baptist Missionary Society was not only rooted in his missionary theology but also in his deep friendship with Carey. Fuller later compared the sending of Carey to India as the lowering of him into a deep gold mine. Fuller and a number of close friends had pledged themselves to “hold the ropes” as long as Carey lived.

MINISTRY AT KETTERING

The critical role Fuller played in the hyper-Calvinist controversy did not preclude his engaging in other vital areas of theological debate. In 1800, Fuller published The Gospel Its Own Witness, the definitive 18th-century Baptist response to Deism, in particular that of Founding Father Thomas Paine. Famed abolitionist William Wilberforce, who admired Fuller as a theologian and once described him as “the very picture of a blacksmith,” considered it to be the most important of all of Fuller’s writings.

The importance of his theological achievements was noted during and after his life. Princeton (then the College of New Jersey) and Yale both awarded him an honorary Doctor of Divinity, though he refused to accept either of them. Not surprisingly, Charles Haddon Spurgeon did not hesitate to describe Fuller as “the greatest theologian” of his century.

But Fuller was far more than a mission secretary and apologist. During his 33 years in pastoral ministry at Kettering, the membership of the church more than doubled from 88 to 174 and the number of “hearers” was often over a thousand, necessitating several additions to the church building.

His vast correspondence reveals that Fuller was first and foremost a pastor. After Fuller died, there was found among his letters one dated Feb. 8, 1812, which was written to a wayward member of his flock. In it, Fuller lays bare his pastor’s heart when he writes: “When a parent loses … a child nothing but the recovery of that child can heal the wound. If he could have many other children, that would not do it … Thus it is with me towards you. Nothing but your return to God and the church can heal the wound.”

Fuller had remarkable stores of physical and mental energy that allowed him to accomplish all that he did. But it was not without cost to his body. In his last 15 years, he was rarely well. Taken seriously ill in September 1814, his health began to seriously decline. By the spring of the following year, he was dying. He preached for the last time at Kettering on April 2, 1815, and died May 7 at the age of 62.