Peter’s Theology of Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah (1 Peter 2:18-25)

Introduction

The apostle Peter is one of the most prominent of the first disciples of Jesus in the canonical record. He was among the earliest of the disciples of Jesus (cf. John 1:35; 2:1-11; Matt 4:17-22), and quickly became the leader of the band of disciples (Matt 10:1-4), a position he held into the earliest days of the post-resurrection church (Acts 1-15). He is perhaps the most visible of the disciples whose discipleship to Jesus transitions from following Jesus around Palestine in the earthly ministry, to following a crucified and resurrected Master in the earliest days of the post-resurrection church, to ministering to disciples of the risen Jesus in churches in the expanded Greco-Roman world (Asia Minor and Rome). Peter knows well what discipleship to Jesus entailed, and guides the early church into discipleship to Jesus in the post-resurrection age.1 In this article we will be exploring the apostle Peter’s theology of discipleship as found in 1 Peter.2

The Curious Absence of “Disciples” in 1 Peter

But first we must address an intriguing phenomenon: the words for “disciple” (noun μαθητής) and “make disciples”/“discipleship” (verb μαθητεύω) do not occur in 1 Peter. Indeed, those Greek terms do not occur in any of the epistles of the NT (nor the book of Revelation), only occurring in the Gospels and the book of Acts. This leads some, especially Karl Rengstorf, the author of the highly influential article on μαθητής in the Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, to come to the conclusion that the relative absence of the explicit terms for “disciple” in the OT and the absence of the terms for “disciple” and “discipleship” in the epistles of the NT indicate that the concept of discipleship is missing. He states, “If the term is missing, so, too, is that which it serves to denote.”3 He then goes on to suggest that while the word μαθητής was appropriate to use in Jewish circles, when the church spread into the Hellenistic world it would not have been appropriate. He suggests that the term implied, in common Greek usage, a student from one of the philosophical schools. The writers of the epistles therefore avoided it since they did not want to give rise to the idea that Christianity was simply a philosophical movement.4 For this reason, the words “disciple” and “discipleship” did not make their way into the church in the Greek-speaking world and declined in usage in primitive Christianity.5

A Broad Use of μαθητής

Several problems arise with Rengstorf ’s suggestion. First, although μαθητής could refer to Greek philosophical students, it was not a technical term reserved for this usage. Not only were several other terms also used to designate philosophical students, but μαθητής had a much broader use in common, religious, and philosophical circles.6 Discipleship was a common phenomenon in the ancient Mediterranean world. In the earliest classical Peter’s Theology of Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah (1 Peter 2:18-25) 55 Greek literature, μαθητής was used in three ways: (1) with a general sense of a “learner,” in morphological relation to the verb μανθάνω, “to learn” (e.g., Isocrates, Panathenaicus 16.7); (2) with a technical sense of “adherent” to a great teacher, teaching or master (e.g., Xenophon, Memorabilia 1.6.3, 4); (3) and with a more restricted sense of an “institutional pupil” of the Sophists (e.g., Demosthenes, Contra Lacritum 35.41.7). Sophists such as Protagoras were among the first to establish an institutional relationship in which the master imparted virtue and knowledge to the disciple through a paid educational process.

Socrates and Plato objected to such a form of discipleship on epistemological grounds, instead advocating a relationship in which the master directs dialogue to draw out innate knowledge from his followers. Therefore, Plato records that Socrates (and those opposed to the Sophists) resisted using μαθητής for his followers in order to avoid Sophistic misassociations (Plato, Sophista 233.B.6–C.6). But he used the term freely to refer to “learners” (Plato, Cratylus 428.B.4) and “adherents” (Plato, Symposium 197.B.1), where there was no danger of misunderstanding. Hippocrates likewise rejected charging fees for passing on medical knowledge, but he vowed in the famous Hippocratic oath that, in the same way his teachers and gods passed on the art of medicine to him, “By precept, lecture, and every other mode of instruction, I will impart a knowledge of the Art to my own sons, and those of my teachers, and to disciples.”

In the Hellenistic period at the time of Jesus, μαθητής continued to be used with general connotations of a “learner” (Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 23.2.1.13, 26), but it was used more regularly to refer to an “adherent” (Dio Chrysostom, De regno 1.38.6). The type of adherence was determined by the master, ranging from being the follower of a great thinker and master of the past like Socrates (Dio Chrysostom, De Homero 1.2), to being the pupil of a philosopher like Pythagoras (Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 12.20.1, 3), to being the devotee of a religious master like Epicurus (Plutarch, Non posse suaviter vivi secundum Epicurum 1100.A.6). The relationship assumed the development of a sustained commitment of the disciple to the master and to the master’s particular teaching or mission, and the relationship extended to imitation of the conduct of the master as it impacted the personal life of the disciple.

Therefore, the terms “disciple” and “discipleship” were broad enough in their normal usage that the authors of the epistles of the NT did not need to avoid their usage. Other explanations for their absence must be explored.

The Chronology of Acts

Secondly, in the narrative of Acts, Luke allows us to see that the terms for “disciple” and “discipleship” were used commonly to designate Christian believers in Hellenistic Asia Minor (cf. Acts 14:20, 21, 22, 28; 16:1; 18:23; 19:1, 9, 30; 20:1, 30) and in Achaia, the heart of Greece (Acts 18:27). The book of Acts does not record the establishment of the churches in the regions mentioned in 1 Peter 1:1 (i.e., Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia), but their cultural and linguistic interplay with the regions of Pauline church planting assumes similar usage of “discipleship” language. Indeed, Jesus’ command to “make disciples” of all the nations finds remarkable verbal fulfillment in the activities of the early church as the apostles went from Jerusalem to Greek-speaking regions such as Asia Minor. Luke tells us that when going through the pagan city of Derbe in Asia Minor, Paul and Barnabas “preached the gospel to that city and had made many disciples” (Acts 14:21 ESV; my emphasis), using the same verb, μαθητεύω, found in Matthew’s record of Jesus’ Great Commission. Luke goes on to say that “they returned to Lystra and to Iconium and to Antioch, strengthening the souls of the disciples (μαθητῶν; plural of μαθητής; my emphasis), encouraging them to continue in the faith” (Acts 14:21-22 ESV). Luke emphasizes that in Greek-speaking Asia Minor to believe in the gospel message was to become a disciple of Jesus. There was no inherent meaning in the terms μαθητής or μαθητεύω that made them inappropriate for use by converts from Greek-speaking circles. Other terms used in Christianity had different connotations in secular Greek circles than in Christian (e.g., “word=λόγος; “love”=ἀγάπη;“fellowship”=κοινωνία), but Christians did not eliminate their usage. Indeed, Christians often sought to use common terms as bridges to other cultures. One of the positive gains in the application of modern linguistics to Biblical studies is the emphasis that words must be understood in their context, whether written or spoken.7 According to the record of Acts, μαθητήςwas used to designate Christians on all three of Paul’s missionary journeys, which was all throughout the primary missionary extension of the church on Hellenistic soils. The chronology of usage in Acts in the very places where the churches of the Epistles and the Revelation were located overlaps the origin and development of these Peter’s Theology of Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah (1 Peter 2:18-25) 57 churches. The converts in these areas were readily and casually called disciples for quite some time, well into the second century, as we see in the literature of the apostolic fathers, especially, though not exclusively, in Ignatius of Antioch (c. A.D. 35-110).8 The reason for the absence of μαθητής and μαθητεύω cannot be attributed to inappropriateness in Hellenistic circles.

The Type of Disciple was Determined by the Type of Master

Third, Jesus spent much time refining the definition of his form of discipleship within Judaism, because evidence indicates that he used the same terminology that the Jews did. Similar to the usage we indicated above within Hellenism, within Judaism of the first century a.d. several different types of individuals were called “disciples,” using the essentially equivalent terms μαθητής and ידִ מְלַ ּת (talmîd).9 The terms designated adherents or followers who were committed to a recognized leader, teacher or movement. Relationships ran the spectrum from philosophical,10 to technical rabbinical scribes,11 to sectarian,12 to revolutionary.13 Apart from the disciples of Jesus, the Gospels present us with “disciples of the Pharisees” (e.g., Matt 22:15–16; Mark 2:18), who possibly belonged to one of the schools (cf. Acts 5:34; 22:3); “disciples of John the Baptist” (Mark 2:18), the courageous men and women who had left the status quo of Jewish society to follow the eschatological prophet John the Baptist; and the “disciples of Moses” ( John 9:24–29), Jews who focused on their privileged position as those to whom God had revealed himself through Moses.

The type of discipleship within Judaism, Hellenism, and the early church was not inherent to the terms “disciple” or “discipleship,” but rather took the shape that was advocated by the type of master. Jesus took a commonly occurring phenomenon—a master with disciples—and used it as an expression of the kind of relationship that he would develop with his followers, but he would mold and shape it to form a unique form of discipleship, far different than others. As Christianity moved out into the Greek-speaking Hellenistic world it continued to maintain the type of discipleship that Jesus had developed. Jesus developed a relationship with his disciples that was unique to his status as the messianic Son of God, whose disciples would ultimately worship him, an action reserved solely for God with his people (Matt 28:16–17).

The Nature of the Epistles

A more likely explanation for the absence of the terms “disciple” and “discipleship” in the epistles and Revelation focuses on the change of circumstances and the nature of the content of the those writings. Other terms began to be used more frequently that focused on the believers’ relationships, especially to each other, and to a risen Savior. This does not necessarily demand that the term dropped from common usage; it simply stresses that its absence from the Epistles and the Revelation may be explained by the adoption of words more expressive of the state of affairs addressed in that genre of literature. The Gospels and Acts are narrative material, describing in third person the actions of the earthly Jesus and his followers as he prepares them to carry his gospel into the world. The Epistles are letters to churches, written in the first person to fellow believers addressed in the second person, describing relationships with an ascended Lord, with a community of faith, and with an alien society. The Revelation is a vision, narrating the activities of the glorified Lord who brings judgment on the earth before his return in triumph. The genre of literature reflects the terms most appropriate to describe Jesus and his followers.

Μαθητής continued to be an appropriate word to designate adherents to the Master, but since he was no longer present to follow around physically, other terms came naturally into use to describe the relationships of these disciples to their risen Lord, to the community, and to society.14 This is the case in the Epistles and Revelation especially, where the subject matter spoke of the risen Lord, where mutual affairs of believers in the church are addressed, and where the church must define its interface with society. However, we do not see strong evidence that the term disciple was actually dropped from usage. The chronology of usage in Acts in the very places where the churches of the Epistles and Revelation were located overlaps the origin and development of these churches. As we have noted, the converts in these areas were called disciples for quite some time, even well into the second century.

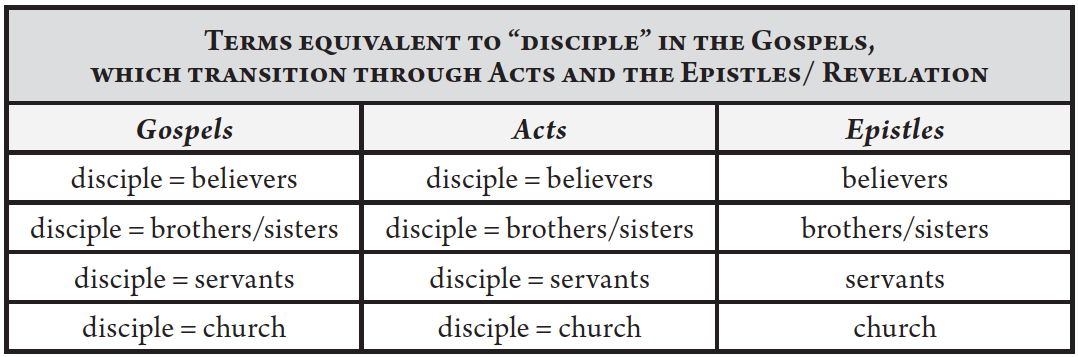

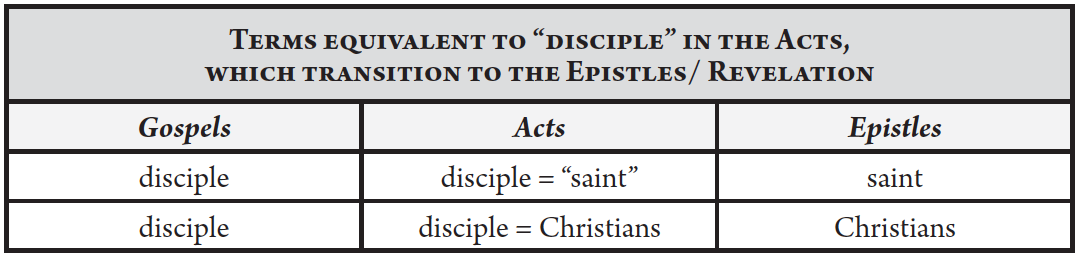

A wide-spread explanation for the absence of disciple terminology suggests that other terms more appropriate to the post-ascension conditions were used within the Christian community. Although “disciple” was still an important term in Acts for describing the relationship of believers to Jesus, a transition to other terms began to occur. One description that naturally expressed the new relationship with the risen Lord was “believers” (οἱ πιστεύοντες, Acts 5:14; οἱ πιστοί, Acts 10:45). Among other names used Peter’s Theology of Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah (1 Peter 2:18-25) 59 to describe the relation of believers to the risen Lord in Acts are “those of the way” (e.g., Acts 9:2) and “Christians” (Acts 11:26; 26:28). Names which indicated the relationship of disciples to one another became very prominent, especially the terms “brothers” and “sisters” (ἀδελφοί, ἀδελφή), which expressed the spiritual family-nature of the new community (e.g., Acts 1:15-16). Where μαθητής does not occur after Acts 21:16, “brothers” comes into use to designate those of the community (e.g., Acts 21:17, 20; 21:7, 17, 20; 28:14-21). An expression which designated the believers’ sacred calling and their relationship to society was “saints” (οἱ ἅγιοι; Acts 9:13, 32, 41; 26:10).

This explanation suggests that the epistles reflect day-to-day concerns of the post-resurrection community. Jesus said that mutual discipleship implied a new family relation of brothers and sisters (e.g., Matt 12:46- 50; 23:8), and the church now experienced that relationship under their risen Lord. Terms which addressed their shared oneness in Christ, such as “brethren” or “saints,” should be expected to be used in the epistles. We therefore see Paul, for example, referring to fellow believers as his brothers/ sisters (Col 1:1/Rom 16:1) and addressing his letters to the saints (2 Cor 1:1), and Peter addressing a fellow-believer as brother (1 Pet 5:12), and referring to the church as the household of God (4:17), and referring to members of the church as his beloved (2:11; 4:12), and Christians (4:16).

This is similar in common usage today. Jesus’ final Great Commission indicated that the outcome of conversion to Christianity is that a person becomes a disciple of Jesus. Therefore, all Christians are disciples of Jesus. However, we seldom address each other as disciples: “How are you, disciple?” Rather we regularly use expressions similar to what we find in the epistles: “How are you, sister/brother?” Pastors address their “beloved flock.” Newspaper articles compare the number of “Christians” in a nation in comparison to the number of Muslims or Hindus.

Therefore, the absence of the words “disciple” and “discipleship” in 1 Peter is a curiosity, but most likely attributable to the general circumstances of the post-resurrection church and the nature of the literature as an epistle offering instruction and admonition in life with the ascended Lord Jesus. With this in mind, we can now turn our attention to how the concept of discipleship occurs in 1 Peter.

Discipleship in Other Words

Jesus had left them. He had comforted them with the promise of the Holy Spirit ( John 14:16-17). He had promised to be with them forever (Matt 28:20). But Jesus was no longer there for his disciples to see, to walk with, to follow as Master. What would discipleship be like in the days that stretched out beyond them? What would it mean to be a disciple of Jesus in the days when he was not with them? Not with them to teach them personally, not with them to correct them, not with them to encourage them, not with them to point the right way.

These were the new days, the new dilemmas, the new crises that faced the fledgling group of disciples whose Master was no longer with them physically. For some of the disciples, this created at first a stumbling-block of faith. Thomas, well known as “doubting Thomas,” had difficulty accepting the news of the risen Jesus. When he finally saw Jesus physically, he confessed, “my Lord and my God” ( John 20:28), one of the most profound declarations of Jesus’ deity in Scripture. But Jesus avowed that the kind of faith that would be needed in the days to come was the kind that would believe while not seeing. “Jesus said to him, ‘Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed’” ( John 20:29 ESV).

We understand the situation of those disciples as they faced a new age when Jesus would not be with them physically, because our situation is so similar. We do not have Jesus here with us physically to follow. For some of us this is a stumbling-block of faith. Forsome of us this means the blossoming of a real life of faith following our Master in the day to day activities of life.

The apostle Peter understood this concept clearly. He gave his readers an example of how to handle suffering in their day to day lives. The example is Jesus. Peter writes, “But if when you do good and suffer for it you endure, this is a gracious thing in the sight of God. For to this you have been called, because Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example, so that you might follow in his steps” (1 Pet 2:20-21 ESV).

We are well aware of the obvious fact that our Master is not here for us to follow around physically. Yet in the example and teaching he provided in his earthly ministry, Jesus still leads the way in our world today. Peter and the other apostles had walked with Jesus in his earthly ministry, and the passion of their ministry was to bring Jesus alive in the hearts and lives of Peter’s Theology of Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah (1 Peter 2:18-25) 61 those around them. That is the meaning of discipleship.

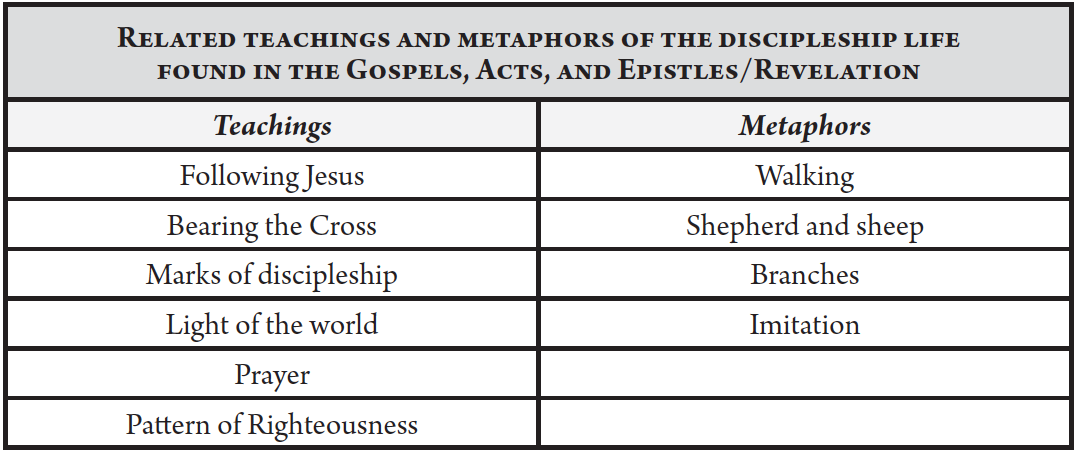

It is this kind of language that compels us to respond with a resounding “Yes!” to the question of whether or not the concept of discipleship is present in the epistles. The consensus in the history of the church—ancient and modern—is that the concept of discipleship is apparent everywhere in the NT, from Matthew through Revelation. While scholars’ emphases and methods of inquiry vary, virtually all scholars now agree that the concept of discipleship is present everywhere in the NT in related terminology, teachings, and metaphors.15 The following charts emphasize that relationship.

For the community that Peter addresses, like for us on this side of the cross, a certain amount of restatement of discipleship as found in the Gospels is needed. Discipleship as it unfolded in the earthly ministry of Jesus as his disciples followed him around the Palestinian countryside must be adjusted in the age of the early church, and today, to having an ascended Master who is now at the right hand of the Father. Jesus developed a form of discipleship in his earthly ministry that was unique, and by the time he issued his Great Commission to “make disciples” of all the nations, his followers knew what his kind of disciple would look like, and what the life of discipleship to the ascended Jesus would look like.

I define discipleship to Jesus in his earthly ministry, as well as in Peter’s experience in the early church in Jesus’ ascended ministry, as follows: Discipleship means living a fully human life in this world in union with Jesus Christ, growing in conformity to his image as the Spirit transforms us from the inside-out, nurtured within a community of disciples who are engaged in that lifelong process, and helping others to know and become like him.

Peter’s Theology of Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah

With this definition in mind, we can outline briefly what we might understand to be Peter’s theology of discipleship to the Crucified Messiah, focusing initially on 1 Peter 2:21-25, but then broadening to include 1 Peter generally. Scholars have noted allusions to the teachings of Jesus in 1 Peter, with some especially noting that these allusions refer to contexts in the gospels that are especially associated with the apostle Peter.16 To take that one step further, the connection of 1 Peter with the teachings of Jesus and Peter’s involvement helps draw a connection with Peter’s experience of burgeoning discipleship to the earthly Jesus with Peter’s articulation of discipleship to the ascended Jesus. The same Peter who brashly tried to prevent Jesus from suffering and dying (cf. Matt 16:21-23), is now the tested apostle who declares that “Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example, so that you might follow in his steps” (1 Pet 2:21 ESV). This is at the heart of Peter’s theology of discipleship to the Crucified Messiah. This can be unpacked in six brief points.

1. Grounded in a Personal, Costly Relationship

The starting point for Peter’s theology of discipleship is that it is grounded in a personal, costly relationship to the Crucified Messiah. Discipleship to Jesus is costly; it cost Jesus his life, and it costs us ours. Although it is nothing we can buy, it is costly nonetheless. The cost is life. Jesus’ life, and our life. This Peter’s Theology of Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah (1 Peter 2:18-25) 63 is perhaps the central point of our passage, and extends the tradition found in Jesus’ words in Mark’s Gospel. “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake and the gospel’s will save it” (Mark 8:34-35 ESV). Peter states, “He himself bore our sins in his body on the tree, that we might die to sin and live to righteousness. By his wounds you have been healed” (1 Pet 2:24 ESV).

Thomas Schreiner comments, “The verse begins, then, with the basis upon which believers are forgiven: Christ’s atoning death. Peter then emphasized the purpose of his death: so that believers will live a new kind of life.”17 Paul Achtemeier extends that thought, “What is evident is that our author sees in Jesus’ death a vicarious suffering by which a new life freed from sin is made possible, a theology already nascent in the description of the suffering servant in Isaiah 53 from which this verse is largely drawn.”18

The verb πάσχω (“I suffer”) is a favorite of Peter, occurring twelve times in this little letter,19 nearly thirty percent of the total of forty-one occurrences in the NT. Likewise, the noun πάθημα (“suffering”) occurs four times in 1 Peter (1:11; 4:13; 5:1, 9), twenty-five percent of the sixteen times the noun occurs in the NT. Those percentages are one of the clues as to the importance of the theme of suffering in this letter. Suffering is a common phenomenon of life, but there is purpose in Jesus’ suffering, and there is purpose in suffering in the lives of those for whom Jesus suffered. The purpose (ἵνα) of Christ’s death was to empower his people “to live for righteousness” (2:24), not in the forensic sense, but in the sense of transformational discipleship; living to righteousness by dying to sins, an experiential relationship with Jesus that brings freedom from bondage to sin (cf. 1:17–19).20 Discipleship to Jesus is a costly relationship.

2. Originates with Gracious Call

Peter emphasizes that discipleship to the Crucified Messiah originates with a gracious call from Jesus to enter into an intimate relationship with him in the midst of the readers’ suffering. The verb “called” (ἐκλήθητε) here (cf. 1:15; 2:9; 3:9; 5:10), along with the noun “called,” “elect,” or “chosen” (ἐκλεκτός) (1:1; 2:4, 6, 9), are significant in Peter’s understanding of discipleship. On one level, this refers to the beginning practice of Jesus as he called individuals to follow him (Mark 1:20; cf. 2:17). In Rabbinic circles and in Greek philosophical schools and the mystery religions, a person made a voluntary decision to join the school of the master and in so doing became a disciple. With Jesus it was his call that was decisive. From the beginning of his public ministry Jesus called, and individuals were faced with the decision either to follow him as his disciple, or turn away. Rengstorf states that “This aspect dominates all the Gospel accounts of the way in which they began to follow Jesus.”21

This was Peter’s own experience, as he was one of the first individuals that Jesus called, along with his brother Andrew and the brothers James and John, the sons of Zebedee (cf. Mark 1:16-20). This is far different than other forms of discipleship in the ancient world, which were largely oriented toward learning a profession or entering into a school or religious training. As in our day, an apprentice entered into the relationship with the goal of one day becoming a master craftsman or teacher.22 But with Jesus, he called men and women into a relationship with him in which he would always be the Master and Teacher.

On another level, the expression “called” will come to refer theologically to the divine activity in which God is the Savior who seeks the sick and the sinners. This activity was revealed early in Jesus’ ministry when he was questioned by the religious leaders of his day why he was dining with tax-collectors and sinners. Jesus’ reply was that, “It is not those who are well who need a doctor, but those who are sick. I didn’t come to call the righteous, but sinners” (Mark 2:17 CSB17). This became the identifying expression, so that in Jesus’ use the noun “elect” or “chosen” (ἐκλεκτός) was essentially synonymous with the term “disciple” or “believer”: “And if the Lord had not cut short the days, no human being would be saved. But for the sake of the elect, whom he chose, he shortened the days” (Mark 13:20 ESV; cf. 13:22, 27; Matt 22:14; 24:22, 24, 31).

On still another level, the “call” extends to a purpose of discipleship. J. Ramsey Michaels states, “Contrary to much that has been written on 1 Peter, the call to discipleship in this letter is not a call to suffering, as if suffering in itself was something good. Rather, it is a call to do good—and, furthermore, to do good even in the presence of undeserved suffering, like that faced by Jesus.”23 The referent of the demonstrative pronoun τοῦτο (“this”) in the phrase εἰς τοῦτο γὰρ that fronts 2:21 encompasses all three verbs in the clause at the end of 2:20: ἀγαθοποιοῦντες καὶ πάσχοντες ὑπομενεῖτε: ἀγαθοποιοῦντες (“when doing good”) καὶ πάσχοντες (“and are suffering for Peter’s Theology of Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah (1 Peter 2:18-25) 65 it”) ὑπομενεῖτε (“you remain firm”): For to this you have been called.24 The goal of their calling is to find favor with God by doing good while suffering for it, and remaining firm. This theme—“doing good”—is for Peter a central element of his theology of discipleship. Peter’s readers have been called by grace to do good.

The term χάρις (“grace”) is found ten times in 1 Peter.25 It appears prominently in Peter’s opening salutation to the letter as he gives a prayer/blessing for the recipients: “May grace and peace be multiplied to you” (1:2). The term likewise appears prominently in the epistolary closing, where Peter gives a summary purpose for writing this letter: “I have written briefly, exhorting and bearing witness that this is the true grace of God. Stand firm in it!” These two opening and closing references to “grace” comprise an important inclusio or “bookends” to Peter’s letter and indicate that “grace” is the nature of the letter itself. This letter is an embodiment of the gospel; it is a gift and it is enablement to live the gospel.

Thus Peter’s theology of discipleship to the Crucified Messiah begins with a gracious call from Jesus that then characterizes the ongoing life of discipleship. It is an underserved call that includes the enablement to be and to become and to do all that to which Jesus has called the readers; especially suffering for doing good. Discipleship to Jesus originates with a gracious call.

3. A Spirit Empowered Transformed Identity

Peter’s theology of discipleship to the Crucified Messiah is experienced especially in a transformed identity, an identity that is produced by and grown by the Spirit of God in our new creation in Christ. Peter’s opening exordium is a powerful blessing of God for bringing about a new birth for Peter and his readers: “Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who according to His great mercy has caused us to be born again” (1:3 NAS). In three rapid εἰς-prepositional phrases, Peter indicates that they were born again “to a living hope” (εἰς ἐλπίδα ζῶσαν; 1:3), “to an inheritance” (εἰς κληρονομίαν; 1:4), “for a salvation” (εἰς σωτηρίαν; 1:5). Peter indicates that from the moment of salvation God views us differently. We are his beloved, obedient children who have been born into a new identity as his child (1:14, 23). This new identity in Christ affects all that we are, including the way we see ourselves, the way we relate to God, and the way we relate to others.26

Against the first century AD cultural values of honor and shame Peter illustrates with notable unambiguousness the ways in which Christian identity was forged from Jewish traditions and converted in the generally hostile Roman Empire. For example, David Horrell points to the unique occurrence of the term “Christian” in 1 Peter 4:16, and indicates that “this text represents the earliest witness to the crucial process whereby the term was transformed from a hostile label applied by outsiders to a proudly claimed self-designation.”27 While the surrounding culture viewed the communities of 1 Peter with derision and hostility, Peter calls them to remember that they are born again (1:3, 23) to a new identity as “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession. Once you were not a people, but now you are God’s people” (2:9-10 ESV). These latter metaphors aid Peter in transforming the readers’ identity in how they approach the world and reinforce their experience of election as those who are consecrated and sprinkled (1 Pet 1:1-2), ransomed for holiness (1:13-19), and are living stones and holy priests (2:1-10).28

Christian identity (as a disciple of Jesus) is a transformed identity, an identity that is produced by and grown by the Spirit of God in our new creation in Christ. As Karen Jobes indicates, “Christ is not only essential to the new birth but is central to the Christian’s new life.”29 Three primary characteristics mark this new life:

a) Transformation of the mind to be free like Jesus—Peter states,“For this is the will of God, that by doing good you should put to silence the ignorance of foolish people. Live as people who are free, not using your freedom as a cover-up for evil, but living as servants of God” (1 Pet 2:15-16 ESV). Being “free” means the ability to do the right and good thing, the ability to choose God, to be liberated from sin’s bondage. This comes from being born again to a transformed identity. This was Jesus’ challenge (cf. John 8:31-32), which Peter echoes.

b) Transformation of the heart to love like Jesus—Peter encourages, “Having purified your souls by your obedience to the truth for a sincere brotherly love, love one another earnestly from a pure heart, since you have been born again, not of perishable seed but of imperishable, through the living and abiding word of God” (1 Pet 1:22-23 ESV). This means to experience an unconditional commitment to imperfect people in which we give ourselves to bring relationships to God’s intended purpose. This was Jesus’ encouragement (cf. John 13:34-35), which now becomes central for Peter.

c) Transformation of character to live like Jesus—Peter exhorts, “So put Peter’s Theology of Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah (1 Peter 2:18-25) 67 away all malice and all deceit and hypocrisy and envy and all slander. Like newborn infants, long for the pure spiritual milk, that by it you may grow up into salvation—if indeed you have tasted that the Lord is good” (2:1-3 ESV). This means to experience the sanctifying work of the Spirit (1:2) and the new life unto righteousness that comes through Jesus’ vicarious death (2:24). This was Jesus’ promise (cf. John 15:7-8), which Peter applies to his readers’ experience of the risen Lord.

It is vitally important for Peter’s communities to see themselves from these perspectives. The starting point of transformation is the recognition that they are born again, now as God’s child. That is the starting point for everything they will become: the roles that they will carry out in life, the hurts and the failures they will overcome, the accomplishments that they will achieve. Discipleship to Jesus comes with a transformed identity.

4. Enabled and Guided by the Living and Abiding Word

Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah also emphasizes that it is enabled and guided in all areas of life by the living and abiding Word of God. This is an enablement and guidance by the absolute Truth and the nurturing of the Truth in our heart through the Spirit enabling and impelling us toward growth in Truth. This stems from Jesus’ statement, “If you abide in my word, you are truly my disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free” ( John 8:31-32 ESV). Peter is one of the clearest examples of one who grasped the Word of God completely as the truth that directed his walk as Jesus’ disciple, and he articulated that principle as central to community and personal transformation. He states,

Having purified your souls by your obedience to the truth for a sincere brotherly love, love one another earnestly from a pure heart, since you have been born again, not of perishable seed but of imperishable, through the living and abiding word of God; for “All flesh is like grass and all its glory like the flower of grass. The grass withers, and the flower falls, but the word of the Lord remains forever.” And this word is the good news that was preached to you (1:22-25 ESV).

This means a radical commitment to the authority of the Word of God as the absolute truth about reality. This is not simply the acquisition of truth, but the internalization of truth so that it expresses our world-view, characterizes our values, and conveys our entire lifestyle. As those within the communities that Peter addresses respond obediently to the Word of God that is energized by the Spirit, the newly transformed heart of the person directs transformation from the inside to the outside.

The OT is the Scripture of Peter’s community, especially as it points to salvation in Messiah and his people. Including direct quotations of OT texts, allusions, and echoes picking up OT themes, scarcely a verse in 1 Peter is exempt from OT influence.30 But Peter also echoes Jesus’ teaching throughout his epistle, here in the parable of the soils as he draws upon the image of a “seed” to refer to the Word of God.31 Here, however, the metaphor refers to human regeneration. The imperishable seed refers to the eternal Word of God, and the new birth indicates the spiritual birth that has been generated by this divine, imperishable seed of God’s Word. Thus Peter continues the theme of the exordium in 1:3 where he praises God who has brought about their new birth (ἀναγεννάωin both passages). This is in comparison with birth brought about through a perishable seed, which refers to human procreation, and is compared to the temporal and fragile nature of the flowers of the field. Achtemeier states, “Such rebegetting, in contrast to their original begetting, comes from imperishable seed, with the result that the ensuing life shares the characteristics of the divine and imperishable rather than the human and thus perishable world.”32 The love commanded in 1:22 is thus possible for a believer to exercise because of the “spiritual energy” of this new birth that God has enacted by his imperishable, eternal word.33

This is a link between Jesus’ teaching on discipleship in the kingdom of heaven (cf. Matt 5:1-20) and Peter’s discussion of regeneration and sanctification through the work of the Holy Spirit. The life made possible through the arrival of the kingdom of heaven is described by the apostle Peter as the transformational process of the person who has been born anew by the living and enduring word of God (1 Pet 1:22—2:3). As Jesus’ disciples, and the communities that Peter addresses, face the daily challenges lived in the everyday realities of a fallen world, they must choose to allow the Spirit of God to produce Christ-like characteristics in them.

Discipleship to Jesus is enabled and guided by the living and abiding Word.

5. The Process of Becoming More Fully Human in Families of Faith

Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah is developed through a whole-life, lifelong process of becoming more fully human, and it is carried out in families Peter’s Theology of Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah (1 Peter 2:18-25) 69 of faith. This is a process that is our regenerated humanity being restored ultimately to the full image of God, which God had intended from creation.

Because of being created in the image of God, humans are like God and represent God in a way unlike any other creature (Gen 1:27-31). The image of God is something in our nature as humans, and refers to what we are (e.g., mentally, morally, spiritually, relationally), rather than something we have or do. This is our identity as humans created in the image of God. Sin distorted the image of God in humans by affecting every aspect of our likeness to him, yet the restoration process has begun with our redemption in Christ (e.g., Col 3:10), and will be completed at the end of our own journey.34

As the complete image of God (Col 1:15-20) and the one whose humanity was never spoiled by sin (Heb 4:15), Jesus is the ultimate pattern of human life for our transformational example. Since he is the image of God in its purest sense, he is the appropriate object that we imitate as we are transformed into his image (Rom 8:29). And since he experienced holistic human development (cf. Luke 2:52) as we do, yet perfectly, we have the perfect example in him of what it means to experience fully human transformation throughout the course of our entire life.

Peter surfaces specifically the example (ὑπογραμμός) of Christ’s suffering. His readers are to follow Christ’s pattern and endure whatever suffering comes their way, so that they would “follow in his steps” (ἵνα ἐπακολουθήσητε τοῖς ἴχνεσιν αὐτοῦ; 2:21). Martin Hengel compares “following” Jesus as his disciple to other forms of disciples in the ancient world who follow their own masters. He emphasizes about following Jesus,

Here “following” means in the first place unconditional sharing of the master’s destiny, which does not stop even at deprivation and suffering in the train of the master, and is possible only on the basis of complete trust on the part of the person who “follows”; he has placed his destiny and his future in the master’s hands.35

Schreiner further emphasizes, “As Christ’s disciples, believers are to suffer as he did, enduring every pain and insult received because of their allegiance to the Master.”36

Further, Christian identity is nurtured in communities of faith. Each individual enjoys a personal relationship with Christ that facilitates transformation into his image, but that personal relationship must be nurtured within two primary communities of faith—the spiritual family and the biological family.

The spiritual family is the church. Entrance to discipleship is based on obeying the will of the Father and experiencing the new birth (1 Pet 1:3; cf. Mark 3:31-35), which simultaneously in this age provides entrance to the church. Brothers and sisters in Christ need each other as a spiritual community of faith to stimulate the growth of individuals as well as the body as a whole (1 Pet 5:5-7).

But the biological family continues to play a major role in God’s program. Marriage is a relationship in which husbands and wives mutually nurture each other’s transformation (1 Pet 3:1-7). The responsibility of the church is to equip families so that husbands and wives can nurture each other and so that parents can nurture their own children. And the responsibility of the family is to be the training grounds for the next generation of the church (e.g., 1 Tim 3:4-5; Tit 1:6-7).

God is Father of the family into which Peter’s addressees have been born (1 Pet 1:1-3), and they are to be obedient children (1:14). Submission becomes a significant issue for Peter in our human institutions: “Be subject for the Lord’s sake to every human institution” (2:13 ESV; cf. 2:11-3:12).37 Biological families headed by human husbands and wives are to live out a relationship of mutual submission, honor, and understanding. The discipleship of marriage is lived out in the context of submission to God and other God-ordained social relationships. The voluntary submission of Christian wives to their husbands is a specific application of 1 Peter 2:13-17, which is the overriding principle of the discipleship of submission.38 This is the countercultural Christian value that believers are to be in submission to one another, which we also see in Paul: Ὑποτασσόμενοι ἀλλήλοις ἐν φόβῳ Χριστοῦ (Eph 5:21).

I understand submission to be a positive placing of one’s will under the will of another so that a higher goal may be accomplished. In the case of Christians, this especially means God’s higher goals. Another way of expressing it may be: yielding my autonomy to serve another so that God’s higher purposes can be accomplished. All humans are created equal, but each has specific roles assigned by God for accomplishing his will. Leadership in this world is a derived responsibility and all earthly leadership is ultimately derived from God. Therefore, to obey earthly leaders is to obey God who Peter’s Theology of Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah (1 Peter 2:18-25) 71 works through them. Submission means placing one’s autonomous will under the will of another, and allowing that person to be responsible for the direction the relationship takes in following God’s will for the relationship. I suggest that mutual submission of believers to one another is the standard principle, which is then to be displayed within various relationships, such as household slaves to master (2:18), the marital relationship (3:1-7), and the church (5:1-5). It is important to balance the responsibility of mutual submission with the responsibility of leadership roles.

Biblical submission does not indicate inequality. The Bible teaches clearly that women and men are equal creations of God: both are made in his image (Gen 1:26-27), both have equal access to salvation (Gal 3:28), and both are fellow heirs of the grace of life eternal (1 Pet 3:7). Submission does not indicate inferiority, but rather points to different roles for men and women. Husbands and wives are in mutual submission to each other as brothers and sisters in Christ, yet for wives to submit to a leadership role of husbands does not indicate that they are of lesser value. And Peter provides one of the most dramatic statements about the connection of personal formation and the biological family, indicating that husbands who abuse the relationship with their wives will have a hindered prayer life (1 Pet 3:1-7).

Discipleship to Jesus is developed through a whole-life, life-long process of becoming more fully human in two families of faith, the church and the biological family.

6. Sojourning Experienced in our Everyday, Watching World

Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah is carried out by sojourning in our everyday, watching world, which is a sojourn that flows from our rootedness in Jesus as he walks with us in the real world.

Peter is one who comprehended the unmistakable reality that he must take hold of his calling as Jesus’ disciple to be witness to the world of the forensic and transformational good news of the kingdom of God. “Beloved, I urge you as sojourners and exiles to abstain from the passions of the flesh, which wage war against your soul. Keep your conduct among the Gentiles honorable, so that when they speak against you as evildoers, they may see your good deeds and glorify God on the day of visitation” (1 Pet 2:11-12 ESV).

The recipients of this letter are identified in the first verse as “the chosen sojourners of the dispersion” (ἐκλεκτοῖς παρεπιδήμοις διασπορᾶς). The adjective “chosen” or “elect” (ἐκλεκτός) identifies them as God’s chosen people, linking them with the people of Israel in the OT, but now alluding to their status as those who have been chosen in Christ Jesus to form the new people of God (2:9). As “chosen sojourners” the readers are visitors in the world because of their special relation to God through Jesus Christ, knowing that God has called them out of the darkness of the world—i.e., temporary residents in this world. And further, the readers are “chosen sojourners of the dispersion.” The noun “dispersion” harks back to the people of Israel, who, because of their sin were dispersed among the Gentiles. It later was used more generally, and less pejoratively, to refer to Jews living outside Palestine ( John 7:35), a theme that James applies to Jewish Christians living among the Gentiles outside of Palestine ( James 1:1).

In recent years a debate has ensued as to whether Peter means this description literally or metaphorically. That debate does not concern this article significantly, but I lean toward Peter using the expressions “elect sojourners of the dispersion” (1:1) and “aliens and sojourners” (2:11; παροίκους καὶ παρεπιδήμους) to indicate that the recipients are members of the kingdom of heaven, which is established in part on earth (cf. Matt 4:12-20; 13:24-30, 36-43), but is not fully established as it will be when the King returns. Believers today are members of that kingdom, so when the world sees us it sees the kingdom. We are sojourning as members of the kingdom in this world while we await the full establishment of the kingdom.

In this earthly life, a human is a sojourner, a resident alien (Ps 39:12). The creation awaits its renewal and it groans under bondage to sin and decay (Rom 8:19-22). Regenerated Christians, however, live as people who have been set free from death and sin; our transformation has already begun. Therefore, we are at this time not of this world; our citizenship is in heaven (Phil 3:20). But we were created for an earthly existence and while we await the establishment of the kingdom of God on earth, we are aliens and strangers in the world (1 Pet 2:11).

Nonetheless, our purpose for being here is to advance the gospel message that has redeemed and transformed us, to be salt and light in a decayed and dark world, and to live out life in the way God intended life to be lived before a watching world (cf. John 17:15-21). Communities Peter’s Theology of Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah (1 Peter 2:18-25) 73 of faith are necessary for purposeful gathering away where believers are strengthened and equipped. But the growth and transformation that we experience is what enables us to live effectively with Jesus in this world. Our transformation enables us to live as sojourners in the world, and “live such good lives among the pagans that … they may see your good deeds and glorify God” (1 Pet 2:11-12). Transformed disciples bear and exemplify the message of the gospel of the kingdom, offering life in our everyday realm of activities to a world that is dying without it.39

Discipleship to Jesus is experienced by sojourning in our everyday, watching world.

Conclusion

Life with the risen Christ in the church was indeed different from life with the earthly Jesus. However, this survey demonstrates the continuity that the NT writers understood between both phases of his ministry. We saw in the overview of continuity/discontinuity in discipleship methodology from the Gospels to Acts that some scholars suggest that the age of the church requires a completely new form of discipleship. For example, one suggests, “The old relationship of a single teacher, superior to his little cluster of devoted followers, is ended. The training process implicit in the term discipleship is replaced by another.”40 The strength of this argument lies in its emphasis upon the change in relationship that did occur when Jesus ascended. However, to suggest that discipleship is to be defined simply by the picture of “a single teacher, superior to his little cluster of devoted followers” is to overlook the defining process through which the concept went in Jesus’ ministry. Jesus’ disciples were not simply identical to the Jewish form of rabbinical student. The form of discipleship Jesus intended for his disciples was unique, and it was not intended only for the time when they could follow him physically; it was also intended for the time when they would gather as the church.41 Discipleship as a concept is much more expansive than merely certain terms. While the term “disciple” naturally contributes to and describes the concept of discipleship, other related terms, teachings, and images are important as well. Those discussed in this article are some of the ways Jesus provided continuity between his earthly and ascended ministries among his people.

Following in Jesus’ steps is a wonderful picture of discipleship which Peter uses to encourage his readers in the middle of difficult daily circumstances. Peter, who followed in the physical steps of the Master, exhorts us all to continue to follow the ascended Master: “For to this you have been called, because Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example, so that you might follow in his steps” (2:21 ESV). This is the heart of the apostle Peter’s theology of discipleship to the Crucified Messiah.

___

1 For a thorough overview of “canonical Peter” and his own discipleship and his testimony to identity and character formation, see Hans F. Bayer, Apostolic Bedrock: Christology, Identity, and Character Formation According to Peter’s Canonical Testimony (Paternoster Biblical Monographs; Milton Keynes, UK: Paternoster, 2016).

2 The explicit self-identification of the author of 1 Peter as “Peter, apostle of Jesus Christ” (Πέτρος ἀπόστολος Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ; 1 Pet. 1:1) was largely unquestioned throughout much of church history. This is not the place to argue against a large body of Petrine scholars who today, mostly since the 19th century, view that explicit self-identification as false. On the basis of strong internal and external evidence from the earliest days of the church, we will assume here the identity of the author of 1 Peter to be the apostle Peter. For discussion and affirmation of Petrine authorship for 1 Peter, see Karen H. Jobes, 1 Peter (BECNT; Grand Rapids: Baker, 2005), 5-19; Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum, and Charles L Quarles, The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament (Nashville: B&H Academic, 2010), 730-735.

3 Karl H. Rengstorf, “μαθητής,” TDNT (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1967), IV: 427, 459.

4 Rengstorf, “μαθητής,” 459.

5 Cf. also Mark Sheridan, “Disciples and Discipleship in Matthew and Luke,” Biblical Theology Bulletin 3 (1973), 239-242.

6 For an analysis of the use of μαθητής in classical and Hellenistic writings, see Michael J. Wilkins, The Concept of Disciple in Matthew’s Gospel: As Reflected in the Use of the Term Mαθητής (NovTSup 59; Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1988), 11-42. For the following excerpt, see Michael J. Wilkins, “Disciples and Discipleship,” in Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels, 2nd ed., ed. Joel B. Green, Jeannine K. Brown, and Nicholas Perrin (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2013), 202–212.

7 A common error in imprecise “word studies” is to force one historical definition of a term into all contexts. Modern lexicological and semantical analysis has revolutionized such studies, demonstrating how words often have broad contextual concepts. The classic work by James Barr, The Semantics of Biblical Language (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961), has been followed by such works as G. B. Caird, The Language and Imagery of the Bible (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1980); J. P. Louw, Semantics of New Testament Greek (SBLSS; Philadelphia: Fortress, 1982); Moisés Silva, Biblical Words and Their Meaning: An Introduction to Lexical Semantics (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1983); Peter Cotterell and Max Turner, Linguistics and Biblical Interpretation (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1989); Constantine R. Campbell, “Lexical Semantics and Lexicography,” in Advances in the Study of Greek: New Insights for Reading the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2015), 72-90.

8 For discussion of the phenomenon of discipleship in the apostolic fathers of the late first and early second centuries A.D, see Michael J. Wilkins, Following the Master: A Biblical Theology of Discipleship (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1992), ch. 16. The noun μαθητής occurs 9 times in Ignatius: Ign. Eph. 1.2.4; Ign. Magn. 9.1.6; 9.2.3; 10.1.3; Ign. Trall. 5.2.4; Ign. Rom. 4.2.4; 5.3.2; Ign. Pol. 2.1.1; 7.1.5. The verb μαθητεύω occurs 4 times in Ignatius: Ign. Eph. 3.1.3; 10.1.4; Ign. Rom. 3.1.2; 5.1.4.

9 D. O. Wenthe, “The Social Configuration of the Rabbi-Disciple Relationship: Evidence and Implications for First Century Palestine,” in Studies in the Hebrew Bible, Qumran, and the Septuagint: Presented to Eugene Ulrich, ed. P. W. Flint, E. Tov and J. C. Vanderkam (VTSup 101; Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2006), 143–74.

10 Philo, De sacrificiis Abelis et Caini 7; 64; 79.

11 m. ’Abot 1:1; b. Šabb. 31a.

12 Pharisees in Josephus, Ant. 13.289; 15.3, 370.

13 Zealot-like nationalists in Midrash Šir Haširim Zûta.

14 This is a widespread conclusion among many scholars; e.g., Avery Dulles, “Discipleship,” The Encyclopedia of Peter’s Theology of Discipleship to the Crucified Messiah (1 Peter 2:18-25) 75 Religion, Mircea Eliade, ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1987), IV:361-364; Charles H. Talbert, “Discipleship in Luke-Acts,” in Discipleship in the New Testament, ed. Fernando F. Segovia (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1985), 62.

15 Examples of this are found in Fernando F. Segovia, ed., Discipleship in the New Testament (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1985) and Richard N. Longenecker, ed., Patterns of Discipleship in the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996). Cf. Dulles, “Discipleship,” IV:361-364; Paul Helm, “Disciple,” Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible (gen. ed. Walter A. Elwell; Grand Rapids: Baker, 1988), 630.

16 Cf. Robert H. Gundry, “‘Verba Christi’ in I Peter: Their Implications concerning the Authorship of I Peter and the Authenticity of the Gospel Tradition,” New Testament Studies 13 (1966-1967): 336-350; followed by Jobes, 1 Peter, 17-18. For comparison, see John H. Elliott, “Backward and Forward ‘In His Steps’: Following Jesus from Rome to Raymond and Beyond. The Tradition, Redaction, and Reception of 1 Peter 2:18-25,” in Patterns of Discipleship in the New Testament (ed., Richard N. Longenecker; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996), 184-208; esp. 191-193.

17 Thomas R. Schreiner, 1, 2 Peter, Jude (The New American Commentary 37; Nashville: B&H, 2003), 145–146.

18 Paul J. Achtemeier, 1 Peter: A Commentary on First Peter (Hermeneia; Minneapolis: Fortress, 1996), 203.

19 1 Peter 2:19, 20, 21, 23; 3:14, 17, 18; 4:1[2x], 15, 19; 5:10.

20 Cf. Schreiner, 1, 2 Peter, Jude, 145; Michaels, 1 Peter, 149; Achtemeier, 1 Peter, 202–3.

21 Rengstorf, μαθητής, 444.

22 Dietrich Müller, “Disciple/μαθητής,” New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology (ed., Colin Brown; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1975), 1:483-490.

23 J. Ramsey Michaels, “Going to Heaven with Jesus: From 1 Peter to Pilgrim’s Progress,” in Patterns of Discipleship in the New Testament (ed., Richard N. Longenecker; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996), 248-268; esp. 254.

24 Mark Dubis, I Peter: A Handbook on the Greek Text (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2010), 76.

25 1:2, 10, 13; 2:19, 20; 3:7; 4:10; 5:5, 10, 12.

26 See Bayer, Apostolic Bedrock, 202-204.

27 David G. Horrell, “The Label Χριστιανός: 1 Peter 4:16 and the Formation of Christian Identity,” Journal of Biblical Literature 126.2 (Summer 2007): 361-381, specifically 362.

28 Nijay K. Gupta, “A Spiritual House of Royal Priests, Chosen and Honored: The Presence and Function of Cultic Imagery in 1 Peter,” Perspectives in Religious Studies 36.1 (2009): 61-76.

29 Jobes, 1 Peter, 47.

30 D. A. Carson, “I Peter,” in Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament (eds., G. K. Beale and D. A. Carson; Grand Rapids: Baker, 2007), 1015.

31 Mark uses the verb σπείρω (Mark 4:14-20), while Peter uses the related noun σπορά. For additional discussion see Carsten Peter Thiede, “The Apostle Peter and the Jewish Scriptures in 1 & 2 Peter,” Analecta Bruxellensia 7 (2002): 145-155.

32 Achtemeier, 1 Peter, 139.

33 Jobes, 1 Peter, 125.

34 For recent discussion, see Ryan S. Peterson, The Imago Dei as Human Identity: A Theological Interpretation ( Journal of Theological Interpretation Supplements 14; Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2016).

35 Martin Hengel, The Charismatic Leader and His Followers (trans., James Greig, 1968; New York: Crossroad, 1981), 72 (emphasis original).

36 Schreiner, 1, 2 Peter, Jude, 142.

37 Peter H. Davids, A Theology of James, Peter, and Jude (Biblical Theology of the New Testament; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2014), 171.

38 See James R. Slaughter, “Submission of Wives (1 Pet. 3:1a) in the Context of 1 Peter,” Bibliotheca Sacra 153 ( January-March 1996): 63-74.

39 See Torrey Seland, “Resident Aliens in Mission: Missional Practices in the Emerging Church of 1 Peter,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 19.4 (2009): 565-589.

40 Lawrence O. Richards, A Practical Theology of Spirituality (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1987), 228.

41 Like some other scholars, Richards dichotomizes the ages of Jesus’ earthly ministry and the church. Richards’ proposal has three basic difficulties. We have addressed these difficulties earlier. First, he commits the common error of placing too much emphasis upon parallels between the rabbinic form of discipleship and Jesus’ form. Second, he does not emphasize enough the distinctive progression in discipleship as initiated and developed by Jesus throughout his ministry and into the church. Third, he does not recognize the continuity/ discontinuity tension between the gospels period and the early church.