Adolescent Moral Development in Christian Perspective

A series of recent and ongoing research studies are exploring the nature and extent of intellectual and ethical maturation among pre-ministry evangelical undergraduates at varying institutional types. This line of research represents the most in-depth analysis ever conducted among this population with regard to epistemological development—i.e., students’ maturity in their ways of thinking, reasoning, and judgment, as well as in their personal commitments to ways of living that exhibit a reflective consistency with the biblical worldview. This article highlights a number of prominent and notable common themes identified in the findings of this research as bearing relevance to pre-ministry undergraduates’ epistemological development, personal formation, and Christian discipleship. Also, the nature and impact of varying social-environmental conditions among pre-ministry college students is addressed.

Research Context

The findings and themes presented in this article are drawn from the initial study[1] in an ongoing series of qualitative research studies, in which pre-ministry undergraduates from three institutional contexts were interviewed according to a standardized semi-structured interview protocol.[2] The three institutional contexts included secular universities, confessional liberal arts universities, and Bible colleges. Thirty students, including ten from each context, were interviewed. This study thus served to initiate precedent findings for subsequent studies to augment and deepen lines of inquiry and investigation among this population. Currently, follow-up studies are being conducted in each of the three original contexts, and additionally among pre-ministry undergraduates and evangelicals attending non-confessional liberal arts universities, two-year colleges and universities, and evangelical seminaries.

While the Perry Scheme of Intellectual and Ethical Development[3] served as an interpretive lens for the study, the researcher introduced the “Principle of Inverse Consistency” as a paradigm for critically interacting with Perry and other developmental theories.[4] Additionally, an original methodological contribution of the study was the design and implementation of a new content analysis framework for identifying and qualifying various elements of epistemological positioning. This framework articulates three categories within which epistemic priorities and competencies may be categorized: (1) biblically-founded presuppositions for knowledge and development, (2) metacognition, critical reflection, and contextualistic orientation, and (3) personal responsibility for knowledge acquisition and maintenance, within community.[5]

In addition to the findings gleaned from this structured analysis, the research yielded a number of prominent, common, and epistemically-formative themes that emerged directly from participants’ articulations related to their particular institutional environments. The significance of these themes was determined according to consistent recurrence among interviewees within or across differing institutional types. Relatedly, categories of pre-ministry students’ perspectives and positions on various issues germane to the college experience were discerned. These themes, identified in the original study and currently the subject of intentional exploration in the ongoing research, are recounted in detail below.

Pre-Ministry Undergraduates

The body of literature comprised by studies on the topic of undergraduate epistemological development is well-established and wide-ranging. Prior to the initiation of this line or research, however, no study addressed the distinctiveness of varying types of institutions in affecting or promoting epistemological maturity among evangelical students, nor had any study specifically engaged the population of pre-ministry college students with regard to intellectual and ethical development. This population represents a diverse range of college students who experience cognitive maturation, identity-formation, social assimilation, and professional preparation in markedly differing environments, depending on which type of college they attend. Given the formative nature of the college years[6] and the essentiality of environmental factors in human development,[7] the influence of institutional types represents a topic worthy of exploration with regard to pre-ministry undergraduates’ worldview, identity, and lifestyle.

Unlike many professions that require mastery of specified disciplines of study on the undergraduate level, there are no specific prerequisite degree requirements for pre-ministry students, regardless of whether or not they enroll in seminary. The result of this is that students preparing for a career in ministry develop their epistemological priorities and values while immersed a number of different institutional contexts—contexts which, by their diverging nature, have unique formational influences and manifestations. This initial study along with its follow-up studies are investigating the nature of these divergences and the resulting effects on pre-ministry students’ maturation.

Significant Recurring Themes

The general findings of the structured content analysis procedures undertaken in the initial phase of this research indicate that overall, epistemological positioning is generally consistent among pre-ministry students from differing institutional contexts.[8] By certain measures, however, positional ratings among institutional groupings are appreciably distinguishable.[9] Extending from the structured analysis protocols, a priority for this series of research studies is the identification of recurring themes that illuminate the impact of differing social-academic environments and cultures on pre-ministry undergraduates’ epistemological perspectives and values. Unlike the findings based on the structured analysis, differentiations between the epistemological expressions of participants from varying institutional types are readily apparent with regard to these prominent themes. The following is a summary of notable themes derived from the initial research study in this series.

The Primacy of Relationships

The most prominent common theme that voluntarily emerged among participants in this study was the primacy of relationships as the most significant single, formative aspect of the overall college experience. Among multiple instances of coordination, this finding most specifically harmonizes with one of the most prominent and definitive works in higher education literature–Astin’s What Matters in College? Four Critical Years Revisited. Astin’s extensive, longitudinal study suggests two key realities regarding the influence and impact of relationships during college: the nature of faculty-student relationships strongly affects both the quality of higher education and students’ satisfaction and appreciation of their college experience; and, “The student’s peer group is the single most potent source of influence on growth and development during the undergraduate years.”[10] Both of these findings were clearly reflected in this study, though with different emphases according to institutional affiliation.

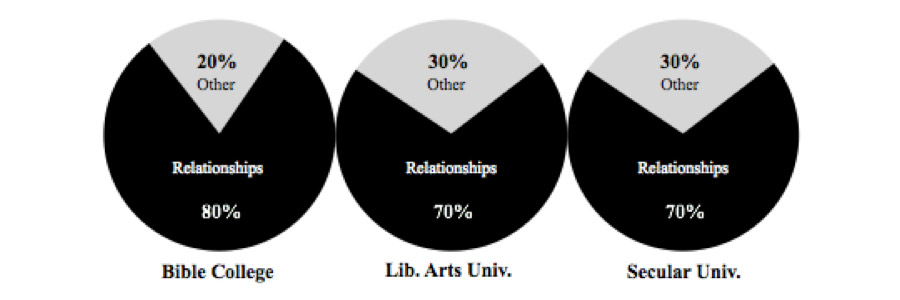

Following Perry, the researcher began each interview with the general question, “Thinking back through your college experience overall, what would you say most stands out to you? What was most significant to you?” In response to this question, nearly three-fourths of responses were predicated on the primacy of relationships, including eight Bible college students, seven liberal arts university students, and seven secular university students. Figure 1 illustrates the striking majorities of students from each institutional context who stated that their college experience was most significantly defined by their relational connections and experiences.

Figure 1 illustrates the striking majorities of students from each institutional context who stated that their college experience was most significantly defined by their relational connections and experiences.

While a majority of all participants cited the primacy of relationships as the most definitive element of their overall college experiences, differentiations were apparent among sample groupings. Of the seven Bible college students who referred to their relationships as most significant, all but one of them spoke specifically of their relationships with professors. Ashley[11] was a recent Bible college graduate who compared the benefit of the relational connections between students and teachers at Boyce College versus a lack of connection at other schools with which she was familiar or had personal experience.

Figure 1. Initial Responses to “What most stands out to you about your college experience?”

Just being able to come to a college where the professors are investing daily in their students and wanting to genuinely help them through college. Any other college I had been to, it was just like you come, you go, and the professors don’t really care unless you come to them. It was just really nice to have that relationship with the professors at Boyce, and know that they aren’t just there to teach, but they want to see you grow in your walk with the Lord and in every aspect of the ministry that you’re going into.

Of the seven liberal arts university students who cited relationships as the most significant aspect of college for them, a wide range of variation was evident. Students spoke about several different avenues of relational connection, including relationships with professors, mentors, peers or close friends, church, campus life connections, and dating relationships. Jacob commented on the link between the genuine peer relationships he had through his college’s residential community and the solidification of his own calling, as well as identification with the body of Christ. He responded in this way when asked by the researcher about how his residential community experiences impacted his life such that he would not have been the same otherwise:

A big part of it is just realizing different approaches on the Christian life. If I would’ve stayed at home I would’ve been around a lot of the same people I grew up with. Being able to come here to college and being thrown into an atmosphere where not only do people have different backgrounds as far as denominations go, but also the fact that I’m a Bible major and a lot of my friends are engineers and science majors. I’ve always enjoyed science, but how they view and live out their Christian life, what they hope to do and accomplish in life as an engineer or as a business man–it’s just a different view that I might have, considering I’m going into full-time ministry. And I think it’s really challenged me to step back and reconsider, “Why am I going into full-time ministry? How can I use business and other contexts that I have to best glorify and best help the Kingdom, working together as a community of believers. Just being able to talk about differing subjects and even conflicts that we may have, but realizing that we’re still the body of Christ and working through it to really understand each other better and understand the issue better.

Responses from secular university students who emphasized the defining significance of relationships in their college experiences all centered on the nature of belonging and developing within authentic Christian community. Some of these responses emphasized relationships with campus ministry leaders in particular, but each focused more broadly on the significance of maintaining a bond of Christian community within the secular university context. Adam spoke about how his active involvement in the Baptist Collegiate Ministry (BCM) at his school facilitated his spiritual awakening, development, and discipleship mentality, coming from a non-Christian background.

The people there (BCM Bible study group) realized where I was coming from, and I told them about my spiritual background, so they held me accountable. They kept me in check in making sure that I was doing fine. They constantly asked me if I was doing okay—wanting to help me out with anything I was having trouble with. And I opened up to them, which is something that I never did with anybody, even in my own family. . . . Since then, I’ve become a lot more of an outgoing person. I used to be really shy. . . . As I went along in my college career, I started to turn my attention more towards the people around me and how they were developing.

Mentors

Another prominent theme that was intentionally addressed in almost every research interview was the influence and importance of mentors. The researcher asked interviewees whether or not they had a mentor relationship during college, and all but four respondents confirmed that they did. Most commonly in each sample grouping, students’ mentors were pastors or ministry leaders. Five Bible college students and five liberal arts university students reported that their mentors were pastors or ministry leaders in their local churches. In contrast, mentors for each the six secular university students who reported having pastoral-type mentors were campus ministry leaders.

Alex was a liberal arts university student whose primary mentoring relationship was with his pastor, but he also reported having mentor-type relationships with some of his peers and teachers. He said this when asked about the sum impact of his mentoring relationships:

There is just absolutely no way to quantify the impact. There’s things that I think and do that I might not ever know why I did them, but it very well could be because of what I’ve been taught by those guys, and how I’ve seen them live their lives. So I think it’s just kind of impossible to quantify the sum impact, but I will say that those guys and the relationships that I’ve been in have forever changed my life. Ask me in 45-50 years if I’m still kicking, and I’ll still probably tell you something similar.

Joseph, a Bible college student, also spoke about the overall value and impact of having a mentor during college.

You can learn so much from a book; you can learn great philosophy from a book; but if you really want to learn practical things, and if you really want to learn real things that can genuinely, directly help you, you really need a mentor to guide you through it. Their wisdom and guidance are invaluable, because they’ve been through ministry; they’ve done years of this, so nothing really surprises them. They’ve gone through it and they’ve come out the other side. And they know you as well, which is something that a lecture or a book really can’t help. They personally know you, your situation, and they know the best way that you could handle something. . . . They can really custom-fit and speak truth into your life.

Jeffrey, a secular university student, emphasized the impact of his mentoring relationship on his holistic development–particularly how the relationship engendered a manner of thinking that is predicated on God’s special revelation.

(Jeffrey) He was my campus minister at the BCM. I can’t remember who actually first introduced this idea–the idea of a three-stranded cord of Paul, Timothy, and Barnabas. You have a Paul figure–a guy that invests in you and pours into you, and a Barnabas figure who is right by your side like your best friend, and your Timothy is the person that you pour into and you see a flow or movement of discipleship through that model. And he was really the first Paul figure that I’ve had in my life–a guy that challenged me. He talked through some tough passages with me, he led me through a lot of things, and he never forced me to think about anything–he let me think more for myself. That was really huge.

(Interviewer) In what ways did you start thinking more for yourself? What do you mean by that?

(Jeffrey) Like, trusting in the fact that the same Holy Spirit that is in him and that’s in theologians is in me, and I can trust in the Holy Spirit as I should trust in the Holy Spirit to speak to me about Scripture, and let God’s Word speak for itself and devote myself to that study.

Some participants reported that their mentors were their college teachers. Among these were four Bible college students and three liberal arts university students. No secular university students reported having mentors who were also their college teachers. One secular university student reported that his primary mentor was one of his peers. Notably, no participants reported that they had mentoring relationships with one or both of their parents.

Relationship with Teachers

The nature of participants’ relationships with their college professors was a theme that provided clear distinctives between students from different institutional contexts. Overall, Bible college and liberal arts university students reported having relationships with one or more of their teachers that were personal, substantive, and dynamic. By contrast, no secular university students reported having a significant personal relationship with their professors. Among Bible college and liberal arts university students, teachers were often referenced as either pastoral influences or personal friends, and sometimes in both respects. Amanda, a Bible college student, said this regarding the pastoral nature of Boyce College professors:

You learn a lot about living life in the ministry and growing in your relationship with Christ and walking with Christ from the professors at Boyce, because they show it and they talk about it and they lead in that way. I feel like it was very beneficial and influential for my personal walk to be under people who were showing us and teaching us how to walk with Christ. . . . Most of them were very pastoral in nature towards us, and it was really neat to see all the stuff that we were learning working out in the immediate life of a minister, and to know that we weren’t just learning something from a book; we were learning stuff that really was being effective in the local church.

Eric expressed his perspective on how having personal friendships with his professors affected his educational experience and personal development.

At Union there’s an underlying, often unspoken, sometimes spoken principle that Christian education is really about more than preparing you to enter into the work force; it’s about training you as an individual and directing you to a certain end. And I feel like I got another level of that training because the same people whose job it was to train me in those aspects–when you enter into a friendship-type relationship in addition to the teacher-student one, the same goals are still there, but it is all the more practical and available in the sense that we spend that much more time together, and we talk about whatever comes up in regular activity. I think just the time and the availability make those goals of education happen all the more. There are that many more opportunities to direct the student to those ends.

Purpose of College

Another clear differentiation emerged among participants from varying institutional contexts with regard to their perspectives on the essential purpose of college. The researcher discerned three categories of perspectives that corresponded to participants’ attendance at their respective types of schools.

Students who attended confessional Christian liberal arts universities, by a proportion of 70% of respondents, expressed that the primary purpose of college is thus: to shape one’s identity as a person, holistically–to establish a mature, authentic lifestyle and manner of thinking. One Bible college student and no secular university students provided this type of response. Numerous expressions on the part of liberal arts university students articulated this priority. When asked about “how students should change as a result of going through college,” Tyler responded in this way: “Their worldviews, their way of thinking, their way of executing their work, their way of studying, their way of handling difficult situations, their way of dealing with people and interacting with people–just all those different aspects of life should’ve changed for the better. The way they view society, the way they view how they act with their friends.” Emphasizing the intellectual-lifestyle objective of college, Jacob said, “College should be a place where you learn how to be a learner.” Kevin summed up the “proper” holistic-developmental priority of undergraduate education by referring to his own experience:

I think one thing college has taught me–particularly a liberal arts college like Union–is learning how to live well, which sounds like a really vague statement. But I’ve learned the importance of making sure that I’m a well-rounded person, appreciating things like music and art, and engaging myself in different cultural mediums–not just combining myself and my learning into one career or into one specific task, but just growing intellectually in the same way that I’m striving to grow spiritually. So one thing that I would hope that students would learn from college is just to have the proper view of education. Unfortunately, I don’t know that all colleges give that.

A secondary theme that emerged among liberal arts university students was that a college education should serve as a means of increasing in knowledge in order to construct a coherent worldview. In recommendation of this prioritization, Thomas said, “A student coming out of high school going into college should end up with a concrete worldview, and should have a consistent philosophy and ideology across the board. What I mean by that is: not pick and choose when to believe certain things; not pick and choose to believe the Bible at times and not at other times.”

Bible college students expressed a different priority regarding the purpose of college. According to 70% of participants within this grouping, the primary purpose of college is thus: to gain knowledge that is applicable, in order to prepare for one’s vocation. One secular university student and no liberal arts students expressed this view.

Among the typical expressions that articulated this view was a statement made by Chris, that the purpose of college “is to prepare you for work in the real world of ministry.” Also, Joseph stressed that college students should maintain involvement in local church ministry and seek out opportunities to learn from mentors. He articulated the purpose of one’s college education in terms of broad, vocation-oriented learning: “Ministry has so many different aspects and so many different elements . . . so you need to learn and take classes and have a working knowledge of every aspect of church and ministry, so you can at least be equipped and it won’t be a surprise to you.” Anthony, a recent Bible college graduate who also had the experience of attending a liberal arts university, provided a perspective that clearly focused on vocationally applicable learning while also integrating the majority liberal arts view of education:

I do feel like an ideal college education involves knowledge being imparted–so yes, intellectual growth. Those categories of knowledge need to be created if they’re not there, they need to be broadened if they’re already there. They need to be challenged and sharpened. But it has to go beyond that. Life-on-life mentoring with professors and mentors is where that knowledge really–where the rubber meets the road and that knowledge can be applied as wisdom. So I would say: transferring of knowledge, life-on-life application of that knowledge such that wisdom is modeled, and then opportunities to apply that knowledge in wise ways oneself. So definitely hands-on ministry–getting messy in the local church. I feel like that is so important for college students to realize. As they’re learning these categories, they need to hit the harsh realities of everyday life. And they need to be sharpened and softened–or hardened–with the reality of messy ministry in the local church.

A clear and unique perspective regarding the purpose of college also emerged among secular university participants. Among this sample grouping, 70% of respondents expressed that the primary purpose of college is thus: to “grow up” or mature in personal (self-identity) and practical (self-responsibility) ways; to increasingly exhibit a sense of personal responsibility regarding education and life. While this view represented more than half of secular university participants, no Bible college or liberal arts university students made any expression related to this priority.

Students from five of the six represented secular universities provided statements that reflected the sample grouping majority. Adam, a participant who became a Christian and committed to vocational ministry during his time at Kentucky State University, said that “a complete, full satisfying college education is one where you find yourself. College is where you split off from everything that you’re used to. . . . You can become you in college.” Similarly, Lauren said, “My college experience has allowed me to get to know myself. I thought I knew myself before coming to college, but I didn’t. I didn’t know a lot about myself, and everyday I find out something new, and I’m just blown away!” In his articulation regarding the primary purpose of college education, Cody summarized the connections between personal responsibility, hard work, devotion to the task of learning in general, and appreciation for the educational process. He said,

A student should gain an appreciation for education. I feel like often middle school or high school students think really dutifully of homework and studying and reading. Because in high school you have homework every night, practically, and you have classes every day for seven hours a day. And in college, usually you get a syllabus that has when your four papers are due and when your four tests are. And you can look at it in a dutiful way, or you can treat it as a job and understand that this is beneficial to you, and you need to read and you need to study and you need to do well. So just having an appreciation for education–I would say that’s as important as whatever degree you get. . . . You need to learn to apply yourself, and you need to care and be intentional about whatever you’re learning.

Impact of College

The researcher was able to discern multiple common sub-themes among participants across and within differing institutional contexts with regard to the overall personal impact of the college experience. While multiple issues and findings explicated in this research coordinated with the results of Pacarella and Terenzini’s comprehensive examination of the effect of the college experience on students, similarities and echoes were most notable in light of these sub-themes. In the most recent volume of How College Affects Students, the authors report that throughout college, “Students not only made statistically significant gains in factual knowledge and in a range of general cognitive and intellectual skills but also changed significantly on a broad spectrum of value, attitudinal, psychosocial, and moral dimensions.”[12] Broadly speaking, the self-reports of the pre-ministry students included in this research indicated that the college experience facilitated a period of personal growth and change that was fundamental, holistic, and permanent. It should be noted that in many respects, the nature of the impact of college on students has been documented to be generally consistent over the past half-century. Pascarella and Terenzini summarize the highlights of this abiding impact for all college students–including (albeit with some inversely-oriented orientations of growth) the participants in this study:

Students learn to think in more abstract, critical, complex, and reflective ways; there is a general liberalization of values and attitudes combined with an increase in cultural and artistic interests and activities; progress is made toward the development of personal identities and more positive self-concepts; and there is an expansion and extension of interpersonal horizons, intellectual interests, individual autonomy, and general psychological maturity and well-being.[13]

In this research, the most general and common sub-theme–articulated by nearly half of all participants–was the recognition that from the beginning of college to the end, he or she became “a completely different person.” This expression was provided by fourteen participants, including seven Bible college students, four liberal arts university students, and three secular university students. Among them was Joseph, a Bible college student who made a clear statement about the fundamental change that he underwent regarding vocational direction, personal maturity, and practical responsibility.

Oh me, I’m a completely different person! As a freshman, I was really unfocused. Ministry was far-off. I was very immature. I knew I wanted to do ministry, but it was far-off, and I just wanted to enjoy college. . . . When I was 18, it was a great blessing that I was able to go to school for free. I could go full-time, I didn’t have to work, so I could just focus on school. I didn’t really have to worry about financing. . . . Now I’m working in a bi-vocational position at a church. The church covers about 60% of what I need, and I work another part-time job about 30 hours a week. I’m a lot more focused, I would say. That would be the key difference: I’m a lot more focused; I’m a lot more mature. In regards to, “This is exactly what I want to do”–I wouldn’t do anything else. This is my passion. This is my desire. I’m a lot more responsible, a lot more mature, and a lot more focused.

Mark, a secular university student who committed to vocational ministry during college, framed his metamorphosis in terms of a shifting view of himself with regard to his sense of overarching purpose and personal motivation.

I feel like I’m a completely different person, almost entirely. My mindset was completely different as a freshman. It was just like, “How can I look the coolest? How can I have the most friends and be in the in-crowd? What can I do to advance myself socially?” And now at the end of college, my heart and my mind are more focused on God and what he wants for my life and how I can serve him. So I think it’s really a huge difference from “how can I serve myself?” to “how can I serve God?”

The most common sub-theme that was directly relatable to participants’ epistemological attitudes and development was evident in multiple students’ expressions that the college experience served to confront him or her with what (or how much) he or she did not know. This expression was identified in more than one-third of all research interviews, including five liberal arts university students, four Bible college students, and two secular university students. While a correlation between this expression and epistemological maturity could not be suggested based on the data acquired in this study, it was observed that most students who provided statements that reflected this perspective received positional ratings in the higher ranges of the sample population. Furthermore, these expressions often provided prime examples of Perry’s concept of “metathought,” or the ability to think about thinking. When asked to elaborate on what he meant by saying that learning was a process of finding out how much he did not know, Robert, a recent Bible college graduate, spoke from his own experience and articulated an implication that addressed the doctrine of progressive sanctification.

From high school to college you realize, “I was really dumb in high school.” That’s your first thought. Then you think, “well, maybe I’m dumb now and I just don’t realize it.” Then sure enough as time goes on you begin to realize that you really do have a lot to learn. So I don’t think I have any of this completely figured out at all. So when I say that “the more I learn, the more I realize I don’t know,” I just mean that I think it’s going to be a long walk and a long process for me to get to where I need to go, and it won’t end until perfection in the New Creation. I just think that I should be learning to be faithful where I’m at, and trusting that I don’t have all the answers. That’s been a big lesson for me to learn throughout my college career.

Richard, a recent secular university graduate who also attended a liberal arts university for two years, provided the clearest articulation of this view. He explained how the recognition of his own lack of complete understanding yielded a spirit of humility that enabled him to apply a new perspective and attitude to his interactions with other believers as well as non-believers.

From my freshman year to my senior year, I really learned how I knew a lot less. When I was a freshman, I was more arrogant–I thought I knew everything, so I didn’t need all this. But as a senior I realized how much I didn’t know. And so I guess I really learned a lot more humility . . . . Through my years of college, God really showed me how much I didn’t know, how much I needed to change my own life, and my own personal character flaws that I needed to address. So as a freshman, I was quick to argue, slow to listen, quick to answer, and always all about myself and what I thought was correct. So I was always quick to jump on people if I thought they were wrong on something, because of how much I thought I knew on everything. And now as a senior I really realize how much I didn’t know and how much I don’t know, and I have just learned to be a lot more humble in my interactions with people, and also in just being more gracious in discussions with people with whom I disagree.

A third clear sub-theme that emerged among liberal arts and secular university students regarding was that a decisive impact of the college experience involved the process of gaining more independence and responsibility in practical matters or personal discipline–i.e., gaining a more mature perspective with regard to entering adulthood and the professional world. Half of respondents within the liberal arts and secular university sample groupings provided expressions that reflected this perspective. Notably, no Bible college students put forth this type of articulation. A typical statement representative of this sub-theme was made by Jacob, a first-semester senior at Cedarville University.

I would say the biggest point of responsibility I’ve seen myself grow in is just managing time and relationships. . . . I’ve realized that the things that I’m going to devote my time to need to be things that matter in retrospect to God’s Kingdom and the work that he would have us do as Christians. . . . I think that’s probably the biggest thing–being able to step back and look and see which things in life I should keep pursuing, and which things that, although not necessarily wrong, are just taking up time that could be better used elsewhere.

The fourth sub-theme relating to the overall impact of the college experience emerged among an equal number of students from each of the three institutional context groups in this study was the expression of development from a more legalistic or personalistic perspective to a more authentic, personally-committed, and selfless perspective regarding one’s faith, worldview and lifestyle. Three students from each sample grouping provided statements that reflected this transition. One of the clearest articulations that represented this sub-theme came from Mark, a pre-ministry student who experienced a faith-transformation while attending the University of Louisville:

I had a general understanding of the gospel, of who Jesus was–that he died for my sins, that he rose again–but I don’t think that there was a relationship there. Because it’s not just “I recognize that Jesus exists,” it’s having that relationship with God. I think that I lacked that relationship. I believed that Jesus was the son of God and all those things, but there was no fruit in my life. There was no proof of a changed heart. Being a Christian for me was just like being a good person; like, “If I don’t do this, don’t do that–Jesus tells me not to do those things, so if I don’t do those things I’m a Christian; I don’t drink or smoke like all my friends in high school, so I must be okay.” That was the mentality I had about Christianity. It was very legalistic. Coming into college changed this idea of legalism to the idea of freedom in Christ, and grace, and a relationship with Christ.

One final sub-theme that also emerged among an equal number of participants from each sample grouping was expressed as a transition from a faith and worldview that was accepted or received from one’s parents, church, peers, etc., to a faith and worldview that was personally-invested–i.e., maintaining one’s convictions in a responsible manner.

Three participants from each category provided statements that represented this perspective. Among them was Sarah, a liberal arts university student, who related her own self-confrontational experience:

I had to make a decision: if being a Christian was just something I’d grown up with and something my parents had taught me, or if it was something that I truly and completely believed in. I had to make that decision for myself without anybody there to hold my hand and take me to church, to Bible study, to the BCM where I was going to grow. I had to make the decision to do those things.

Perspective regarding Seminary

One theme that was intentionally engaged by the researcher in almost every interview was participants’ perspectives regarding seminary. All responses were assignable to one of two positions, with the exception of one response by a liberal arts university students who articulated a hybrid-view, incorporating both positions.

A clear majority of all participants were classified as having an “idealistic” perspective regarding seminary–the view that seminary is primarily necessary or beneficial for the knowledge and skills that are to be gained there, in preparation for vocational ministry. Every secular university student maintained this perspective, as well as eight of the ten liberal arts university students, and six of the ten Bible college students. Cody, a secular university student, expressed his personal view that seminary would serve as a necessary completion of his ministry preparation on a formal level, after being trained on an experiential level in college. He said,

It’s necessary for me to go to seminary for knowledge. There’s too many pastors who don’t know why they do what they do. And even me, I’m still figuring it out. As a pastor–as someone who is going to teach the Word of God and who is going to serve in the church the way that God has designed Christians to interact here on earth–you need to know the history of the church and you need to know the Scriptures and how the church should be set up–the polity. You need to be able to counsel people. You need to be wise in the decisions that you make and how you lead the church. I feel like I got plenty of ministry experience serving at Campus Crusade and serving at my church through college, but those are things you have to investigate on your own and what you have to be taught and read.

Alex articulated his idealistic view by expressing his hope that his seminary education would share priorities that are in concert with his idea of a liberal arts education–focusing on “expanding horizons” and interacting with ideas in an effort to arrive at a more informed, reflective set of convictions.

I hope to be challenged. In the same way as Union–I want my horizons expanded. I want to not necessarily arrive at different conclusions, but be exposed to a whole lot of different perspectives along the way to those conclusions. So maybe I go into Southern (seminary) thinking this way about the atonement. I may leave Southern thinking the exact same way about the atonement, but on the other side of Southern, I hope to have been exposed to a lot of different perspectives.

In contrast to the idealistic view, a second categorization of participants’ perspectives regarding seminary was the “practical-utilitarian” view–that seminary is primarily necessary because it is a prerequisite for obtaining employment in a career-type ministry position. Among respondents who expressed the practical-utilitarian view, four were Bible college students and one was a liberal arts university student. Most notably, Aaron expressed his disappointment and frustration because of the virtual “requirement” of a seminary degree in order to be considered as a qualified candidate for employment at most local churches.

I don’t think it’s necessary (to go to seminary), but it is necessary. It’s necessary because churches have such a skewed idea, that you look at almost any requirement, and they require a piece of paper before they think you’re qualified to be a pastor. . . . I’ll be honest with you, . . . I don’t think that seminary, in any way, shape, or form, is going to be very beneficial for me. I would see more of a hindrance than a benefit, in the sense that it’s going to steal more time away from the church I’m already serving at. It’s going to be rehashing all the exact same things we studied at Boyce. . . . I’m very much aware that not many people will hire me without a degree. So I think our society has made seminary necessary. I think biblically and in reality, it’s not, but you’re going to be hard-pressed to find a job in ministry without a degree, because it’s what everyone wants.

“The Bubble”

One final recurring theme that emerged among a significant number of Bible college and liberal arts university participants was identified as the perspective at the root of a common terminological reference–“the bubble.” Nearly half of all Bible college and liberal arts university students included in this study voluntarily used this term in the course of the research interview when discussing the nature of their institutional context. Ashley, a Bible college student who transferred to Boyce college after attending a secular university, referenced the term while acknowledging the danger of losing a real-world perspective within the confines of a strictly evangelical environment. She said,

They warned us when we came into Boyce about the “Boyce bubble.” They said, “You’re going to form this bubble and not want to get out into the real world and be around real people.” And I’ve seen that. If I go home for a weekend and I’m around unbelievers it’s hard to adjust to that, because you’re daily surrounded by believers (at school). So when you’re among unbelievers it’s hard to adjust. It’s almost like culture shock. It’s always hard for me, because when I was in a secular college it wasn’t that it didn’t bother me, but it was nothing to hear girls on my basketball team cuss and swear. And now when I hear those things, it throws me off. In that aspect, I think it’s a drawback–if you get so surrounded by believers everyday and it gives you a culture shock when you go into the real world. I think there should be a balance there. Yes, it’s okay to be around believers but don’t isolate yourself either.

As a liberal arts university senior, Kevin reflected on both the benefits and the costs of his educational environment. He provided this response when asked if he would choose to attend the same type of school again, rather than choosing to experience an institutional context that included a greater diversity of worldviews and confrontational cultural norms.

Absolutely I would. There’s no question about that. For better or worse, Union is the way that it is, and you do miss out on some of those interactions. But at the same time, I’m just extremely grateful for the way that Union approaches learning in general and how it views the intellectual life as something that comes under the authority of Christ. The philosophy that Union has is that learning is something that is ultimately supposed to prepare us to meet God face to face. So that’s something that’s not going to be the focus at secular universities, where you have more learning to equip you for some type of career or task. I don’t think that focus is what it should be. Not to mention, the opposition from professors that you would face, who are skeptical of Christianity, the opposition from other students in the student body, and just the general degenerative environment that unfortunately pervades a lot of secular campuses, where you have a lot of temptations and a lot of immorality going on.

Considering The Impact of Social-Environmental Conditions

A second extension of the structured analysis component of this series of studies is the intentional consideration of the impact of differing social-environmental conditions relating to personal discipleship and formation, life and ministry preparation, and epistemological maturity. To this end, the initial research study in the series analyzed participants’ experiences and perspectives with regard to three particular conditions: challenges to personal beliefs and values, interaction with ideological diversity, and exposure to multiple disciplines. A number of distinctive contextual realities and perspectives stemming from students’ immersion in their respective institutional contexts were uncovered. For pre-ministry undergraduates, these distinctions are likely to influence the trajectory of personal development, the course of epistemological maturity, and the application of gained knowledge and skills in the practice of ministry.

Challenges to Personal Beliefs and Values

The first social-environmental condition explored by the researcher with regard to participants’ experiences within their respective institutional contexts was the nature and impact of personal confrontations with worldviews that served to challenge one’s own beliefs and values. The division between categorical perspectives with regard to students’ experiences was understandably stark. One-hundred percent of secular university students experienced interactions within their educational environments that directly challenged and conflicted with their core, fundamental beliefs. By contrast, no Bible college or liberal arts university students reported such interactions. Sixty percent of participants from both of these sample groupings did report experiencing interactions within their educational environments that posed challenges to their non-fundamental beliefs.

Core, fundamental beliefs. While all secular university students expressed that they had the experience of confronting direct challenges to their core beliefs and values as a result of immersion in their respective institutional contexts, it is important to note that no students reported that they doubted their core convictions as a result. Many did, however, state that engaging with conflicting worldviews served as a means of helping them mature in their own formation and application of the biblical worldview. Adam addressed his appreciation for these confrontational experiences in this way:

I definitely value them now, although at the time it was hard to value them. Looking back and thinking about it, it’s like, “If not for those things that challenged me, I wouldn’t be as confident in what I believe.” So because of these controversial things that came up, I was able to realize and fully develop my own opinion on the matters so that I can be more confident in them. I definitely value them, although they challenged me at the time.

More specifically, numerous students described the connection between their interactions with non-Christian worldviews and cultural norms during college, and the emergence of a missional perspective according to which they began to view their ministry calling. Richard, a recent graduate from Western Kentucky University, articulated such an attitude as he spoke about how challenges to his core beliefs and values led to a more self-invested and responsible personal faith and missional attitude toward doubters and skeptics.

Being exposed to a lot of anti-Christian philosophical arguments, it makes you have to think. It really challenged me in a lot of what I believed. So there was never a point of outright disbelief, like “I’m not entirely sure what I think,” or “I’m not entirely sure what I believe.” But I had to really rely on God and sort things out: What do I believe myself?–not “How was I raised to think?” or “What did everyone else tell me about how I was supposed to believe?” but “What exactly do I see in Scripture and who is the God that I see that exists, and how does he reveal himself?” So it was really that first year at Western, three years ago, when I went through a time of skepticism. And through that time, God really showed me a lot about how I needed to handle people, and he also showed me a lot about what to say to other people that were dealing with a lot of the same things that I dealt with. It was like God led me through that valley to show and teach me a lot, so that now when I deal with people who are at that place like I was, I know what to say, I know much more how to handle what they’re going through.

Non-fundamental beliefs. Among Bible college and liberal arts university students, 60% of respondents reported experiencing challenges to non-fundamental beliefs, but not core beliefs. Among these was William, a recent liberal arts university graduate. He provided a very thoughtful and reflective articulation regarding the experience and benefit of interacting with varying theological and philosophical perspectives while maintaining an openness to having his own perspective revised–within the bounds of orthodoxy.

There are a lot of incorporations of philosophy that the church throws out very often, even some postmodern ideas, or post-structuralistic or whatever you want to call it. And for me, the requirement to engage with those ideas was really good because it made me think about how I have been taught or asked to swallow the pill of just holistically rejecting those ideas. And I think the reality is that there’s a lot of good knowledge there, and some ideas that line up with biblical thinking. And I think that that is what some of us might call “common grace.” We should not holistically embrace those ideas but dissect them, or, to borrow a term from the times–“deconstruct” them–and realize that conservative ideas hold a lot of good truth, but neither are they holistically true. That led me to think about some maybe academically leftist ideas and pick apart where they might line up with some biblical truths, but also identify where they’re dangerous and where they don’t.

Interaction with Ideological Diversity

The second social-environmental condition intentionally explored by the researcher was the nature and impact of participants’ interaction with interfaith dialogue across varying institutional types. More broadly, this condition addressed the extent to which pre-ministry students’ were exposed to ideological diversity and the level at which they interacted with competing ideologies, according to their respective college environments. Findings regarding this condition were essentially identical to the previous condition.

Oppositional worldviews.

Without exception, every secular university student reported that his or her primary interaction with ideological diversity involved engaging people within the college environment who held oppositional worldviews. Among Bible college and liberal arts university students, one student from each context reported that his primary experience with diverse ideologies during college involved engaging people with non-Christian ideologies. In both of these cases, however, the student’s medium of interaction was completely removed from any campus-based context.

Similar to the findings related to the first condition, a common refrain of secular university students with regard to their encounters with diverse ideologies was that those experiences enabled them to establish and apply a missional perspective. One such expression was provided by Cody, who spoke about how his interactions with diverse worldviews served to frame his perspective about his ministerial calling. Regarding the impact of those interactions, he said,

I would say that the biggest impact it has is that I would have classes with twenty or thirty people, and there might be one other person I know who’s a Christian, but there are eighteen others who aren’t. And you get to have group discussions–especially in the Religious Studies program, where every class is discussion based. You get to have lots of discussions and peer-editing papers, and lots of just going and grabbing lunch with people after class and hanging out and inviting guys to come over and watch a movie–all kinds of different stuff. It just gives you a heart for a broken world. It is living in an environment where you have to be missional minded, because 90% of the people around you don’t believe in the gospel.

Later in the same interview, speaking of how his default perspective toward non-Christians fundamentally changed, Cody said,

Before college I had this view of non-Christians–like they had this disease, and I would have to act differently around them and talk differently around them. And it was the same early in college, like I had to have my guard up to lots of friends that I made that were not believers . . . Kind of this leprosy thing. It took a while to be exposed to it enough to realize I have the same leprosy that they do–the same sickness–to not be scared of the fact that they are an unrepentant sinner, but to really embrace the fact that I also was that. There’s kind of a level ground there, that I had to almost walk up to, or I guess walk down to–where I thought too highly of myself and I thought that these people were weird and I didn’t want to be friends with them; I didn’t want to let them into my life; I didn’t want to know them. And so being at a secular university really exposes that.

Differing doctrine or ecclesiology. A majority of Bible college and liberal arts university students reported that their primary interaction with ideological diversity in college involved engaging other evangelical Christians with differing doctrinal or ecclesiological positions. Eighty percent of liberal arts students responded in this way, as well as 60% of Bible college students. A typical response among participants from these two sample groupings to the researcher’s question, “Did you encounter ideas during college that challenged your own beliefs and values?” was Steven’s. He said,

Yeah, I had a roommate for 3 years that grew up in the Assemblies of God church. I was raised Independent Southern Baptist. So obviously meeting my roommate, we had tons of theological discussions about different ideas. So yeah, I did come into contact with a lot of different beliefs. I even found, after spending some time at some different churches and spending time around the pastors on staff there, a lot people who believe the same thing but emphasize different things. So I always thought that was interesting too. I did get a lot of different beliefs, but nothing that I would’ve ever broken fellowship over. I would say there was definitely more people that I met that believed similarly to me but placed emphasis on different things.

Exposure to Multiple Disciplines

The final condition explored by the researcher addressed exposure to multiple disciplines. This condition was not applicable to Bible college students, since their curricula did not include multi-disciplinary requirements. The researcher specifically asked participants from liberal arts and secular universities about the value and perceived benefit of exposure to multiple disciplines. This was in an effort to potentially discern an identifiable relationship between exposure to interdisciplinary studies and pre-ministry students’ epistemological maturity. Analysis, however, did not reveal any relationship between encountering or valuing interdisciplinary studies and participants’ epistemological positioning. Overall, half of participants from each sample grouping expressed that they felt their experience with multiple disciplines was significant and helpful.

Conclusion: Research Applications

The findings and observations discussed in this article are drawn from the first in a series of ongoing research studies that are exploring the variance of epistemological development and maturity among pre-ministry undergraduates according to institutional affiliation. The completion of current and future follow-up studies will serve not only to fill a void in the area of undergraduate development, but more strategically will serve the church by highlighting the idiosyncrasies, benefits, and drawbacks of differing collegiate environments.

This research directly applies to current or forthcoming evangelical college students who have made (or will make) commitments to pursue vocational ministry. This line of research offers a unique aggregate of perspectives, delivered by the first-person viewpoints of pre-ministry undergraduates from multiple schools across differing contexts, regarding the nature of distinctive collegiate environments as it is related to the experiences of evangelical students in general, and pre-ministry students in particular. Students may utilize this research as a tool for introspection, evaluation of their own current college experiences, and diagnosis of their own trends of discipleship and maturation. Considering the implications presented above regarding the environmental distinctions between contexts, current or forthcoming pre-ministry students may gain an awareness of ways in which they should seek to capitalize on the opportunities provided within their own contexts, as well as ways in which they may seek to expand their personal growth and preparedness for ministry by engaging outside contexts. For example, pre-ministry students in secular college environments may intentionally seek opportunities and methods by which to enrich their knowledge, understanding, and application of biblical presuppositions and key theological concepts and issues—while also taking advantage of the extraordinary opportunities for authentic relational interaction and missional engagement with non-Christians.

In the same way that this research applies to current or forthcoming pre-ministry undergraduates, it also applies to those who advise them and mentor them. Thus, parents, mentors, local church pastors and ministry leaders, campus-based ministry directors, and any others entrusted with influence in the lives of future vocational ministers may utilize this research to inform the wisdom of their counsel.

This research also applies to college teachers, administrators, and student service professionals at higher educational institutions that train future ministers. Teachers may utilize this research to evaluate their effectiveness in facilitating students’ intellectual development and overall maturity, as well as their relational connections with students. Such was clearly demonstrated in this study to be key element of pre-ministry undergraduates’ college experiences. Student service professionals and administrators at evangelical colleges may utilize this research to review their diagnostic methods of evaluating students’ Christian formation, as well as to inform their priorities and practices with regard to encouraging students’ personal maturation. Also for higher education personnel, this research may be utilized as an evaluative tool with regard to the formational efficacy of the institution’s curriculum design and implementation.

Finally, this research applies to seminary faculty and administrators at institutions that receive graduates from varying collegiate environmental backgrounds. This study provides significant insights regarding the variation of epistemic positions and attitudinal perspectives on the part of current and incoming seminarians according to their respective, divergent collegiate experiences—academically, socially, and culturally. Particularly, these insights may be used to inform seminaries’ methods and processes of assimilating and advising prospective and incoming students, as well as new and current students.

[1] John David Trentham, “Epistemological Development in Pre-Ministry Undergraduates: A Cross-Institutional Application of the Perry Scheme” (Ph.D. diss., The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2012).

[2] The full interview protocol is included in the Appendix 5 of Trentham, “Epistemological Development in Pre-Ministry Undergraduates.”

[3] William G. Perry, Jr., Forms of Ethical and Intellectual Development in the College Years: A Scheme (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1970). The Perry Scheme proposes that undergraduates and young adults progress in epistemological maturity by progressing through a series of positions which represent movement away from dualistic forms of thinking in favor of forms that are contextual and relativistic, propelled by decentering encounters with diversity through the college experience. A guiding premise for this line or research is that there is an evident consistency between the pattern of development suggested by Perry and the biblical pattern for transformative maturation unto wisdom through progressive sanctification.

[4] The Principle of Inverse Consistency maintains that a preliminary commitment to the authority and sufficiency of Scripture must be the guiding evaluative premise on which all secular developmental models are assessed. The orderly world is so created by God that secular social science research may accurately observe and identify human developmental patterns and behaviors. The noetic effects of sin are so pervasive, however, that the ability of secular researchers to rightly interpret those patterns is radically limited. Namely due to its anthropocentric disposition, secular social scientific analysis cannot adequately prescribe norms of growth and maturation. Rather than conformity to Christ, positive development is conceived in terms of self-identity or self-actualization. While secular and biblical models may include consistent patterns of maturation, they are oriented toward respectively opposite goals: self and Christ. Inverse consistencies thus exist between the biblical notion of positive maturation and secular developmental notions, which in the the Perry Scheme entails an existentialist form of self-referential identity and commitment.

[5] See Trentham, 128.

[6]The most recent and exhaustive analysis of the influence of the college experience is Ernest T. Pascarella and Patrick T. Terenzini, How College Affects Students: A Third Decade of Research, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2005).

[7]This is described by Lewin’s interactionist equation, B = f (P X E), which is the foundational principle for understanding college student development theory. See Nancy Evans et al., Student Development in College: Theory Research and Practice, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010), 29.

[8] Epistemological position ratings of interviewees were determined according to evaluation and scoring analysis performed by William S. Moore, director of the Center for the Study of Intellectual Development (CSID). The researcher’s original content analysis framework, rooted in biblical presuppositions and focusing on epistemological priorities and competencies, confirmed the ratings of the CSID for each institutional grouping.

[9] For instance, in the initial study, among participants who were five years or less removed from high school, liberal arts university students reflected a distinguishably higher collective position of epistemological maturity.

[10]Alexander W. Astin, What Matters in College? San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (1993), 383-98. See also Astin’s helpful and succinct summary of the study: Astin, “What Matters in College?” Liberal Education 79 (1993), Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 6, 2012).

[11]Personal names of all interviewees have been changed to preserve anonymity.

[12]Ernest T. Pascarella and Patrick T. Terenzini, How College Affects Students: A Third Decade of Research, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2005), 572.

[13]Ibid., 577.