In praise of thanksgiving and the cultural liturgy of “You’re Welcome”

It’s been interesting to think about our culture in terms of its celebration of holidays. Here in Louisville, Halloween has become a big deal. Several streets now feature weeks-long decoration parties, as families and residents try to outdo one another by putting up the most zombies, vampires, and cobwebs. My wife and I, working from…

It’s been interesting to think about our culture in terms of its celebration of holidays. Here in Louisville, Halloween has become a big deal. Several streets now feature weeks-long decoration parties, as families and residents try to outdo one another by putting up the most zombies, vampires, and cobwebs. My wife and I, working from a decidedly different worldview–one that sees no celebration in death, but rather the overcoming of it–tell our kids not to look out the window.

Meanwhile, it’s Thanksgiving week, and we’re all gearing up for Black Friday. Let’s pause and think. Is something wrong with that sentence?

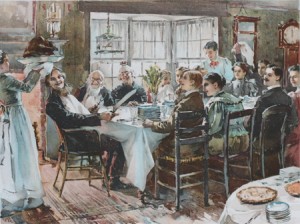

This is not the way I remember it. Growing up in New England, Thanksgiving was a big deal. My family would travel to be with extended family in Massachusetts and Maine. We got out of school early due to the much-cherished “half day.” Then we drove and drove. It’s funny what you remember as a kid. The tightly packed car, cold feet, brief gas station stops, incessant reading with a booklight (I read for hours and hours and hours), and then actually arriving at the destination. Tired but excited. Family all around. Anticipation of being together the next day.

What do we look forward to now? Shopping. Are you kidding me? I have no problem with capitalism. I don’t think it’s bad to buy stuff, or even to shop on Black Friday. I don’t have a guilt complex over the modern economy and my involvement in it. My concern is this: we’re at practically the sweetest moment of the year, a little cherub on the calendar, and we’re more excited as a culture to go to Best Buy than to spend time together? The mall? To fight traffic and be swept over by packs of teenie-boppers? To deal with clerks who understandably want nothing more than to be freed from waiting on us at this very moment?

Again, I don’t think people should feel guilty for purchasing something on Black Friday. Clearly, that’s fine. But if the whole focus of a family in Thanksgiving Week is getting up early enough to buy stuff, and not to thank the Lord for his bountiful kindness, something seems fundamentally askew to me. We’ve missed the mark somewhere.

The sweetest things in life are restorative and others-centered. Thanksgiving exemplifies this. It is a common grace moment to remember God’s special grace. It is about, fundamentally, the Lord. It is a day set aside for him. It is a day not to integrate, to engage, if we can help it. It is a day to rest and be with loved ones. It should be pervaded by a sense that we deserve nothing. God deserves everything. And yet the mystery before us: we have so much. We have so much more than we could ever want or think. This is because of God and his grace shed abroad in Jesus Christ. This is, therefore, his day.

The Pilgrims have fallen on hard times. They were imperfect, to be sure. But the modern deconstructionist impulse that critiques them and belittles them is devastatingly harmful for families and traditions and societies. It eats and destroys and leaves nothing but irony in its place. So do something old-fashioned: read about the Pilgrims (good book for families here). Read about how they gave thanks to God. Celebrate them and their legacy with your family. Don’t make them sound weird or silly or awful. Be thankful to God for them.

The modern deconstructionist impulse has no place for being thankful. It believes it is owed everything by the world. It therefore responds to a sincere “Thank you” with a half-sullen “No problem,” as if you’re temporarily off the hook for having potentially inconvenienced whomever it was that helped you. Do not, my friend, let those vile words escape your lips. Offer back a heartfelt “You’re welcome,” which signifies that a social system of thankfulness and service exists. There’s an entire barrier reef of gratitude and others-centeredness that is being eaten away by modern social philosophy.

Don’t participate in this order of ingratitude. Be old-fashioned. Be weird. Be traditional. Be subversive by being, well, unmodern. Irony has its place. I love irony. But there are places it should not go. It does well as a side dish, but not as a main course (Can you tell what’s on my mind?). It works nicely when there’s an awkward moment, when someone is needlessly wounded, when there’s little good that you can think to say, when an event is so funny it begs for slanted commentary. Irony does not bless us, though, at the funeral, on the wedding day, in the midst of cherished traditions.

So leave irony and cynicism and consumeristic frenzy aside today and tomorrow if you can. It may be that your work, the honorable means of living God has given you, requires you to labor. There is no shame in that. Neither is it wrong to buy stuff. But if possible, set aside some time to rest and pray and enjoy and eat. This is a day of thankfulness. Narcissism and entitlement has no place here. The Pilgrims were not celebrating their worthiness in making it over here. They were setting their hearts like a tractor beam on God and his goodness. So should we.

Unironically, I close with the old King James Version, which so often has the best translation in poetic terms:

The LORD hath done great things for us; whereof we are glad (Psalm 126:3).

*This post originally appeared on Owen Strachan’s blog ThoughtLife.

____________

Owen Strachan serves as assistant professor of christian theology and church history at Boyce College. In addition, Dr. Strachan serves as the Executive Director of the The Council on Biblical Manhood & Womanhood. He is the author of Risky Gospel along with several other titles. You can connect with Owen on his blog or on Twitter.