Christmas 1913: 100 years ago at Southern Seminary

Southern Seminary students and faculty of contemporary times understand the temporary reprieve that comes at the end of the fall semester, perhaps using the extended Christmas break to travel and visit family or catch up on personal reading and research. The campus is a virtual ghost town in the days leading up to and following…

Southern Seminary students and faculty of contemporary times understand the temporary reprieve that comes at the end of the fall semester, perhaps using the extended Christmas break to travel and visit family or catch up on personal reading and research. The campus is a virtual ghost town in the days leading up to and following Christmas. This was not always so.

Southern Seminary students and faculty of contemporary times understand the temporary reprieve that comes at the end of the fall semester, perhaps using the extended Christmas break to travel and visit family or catch up on personal reading and research. The campus is a virtual ghost town in the days leading up to and following Christmas. This was not always so.

One hundred years ago, in 1913, the campus was in the heart of bustling downtown Louisville, Ky., and students were three full weeks into their second quarter. It was the custom for many years not to break for winter holidays, instead offering a prolonged summer vacation of four months, an “opportunity for the students to engage in colportage [selling Bibles] and missionary work.”1 A report from 1893 relates that “a few among [the seminary students] tore away to sit again around Christmas fires … but the larger proportion of students held closely to their work, as though nothing unusual was happening.”2 Not until 1917 did the seminary’s leadership add a two-day break for Christmas.

With most students on campus on Christmas day, the New York Hall dormitory and Norton Hall classrooms would have been buzzing. The seminary community was nearing capacity and plans for a new campus were already in motion. Students living in New York Hall might have found comfort in the steam-heated facilities, but the downtown area in general was plagued by soot and smoke. President Mullins had already moved his family to an eastern suburb out of concern for his wife’s health.3

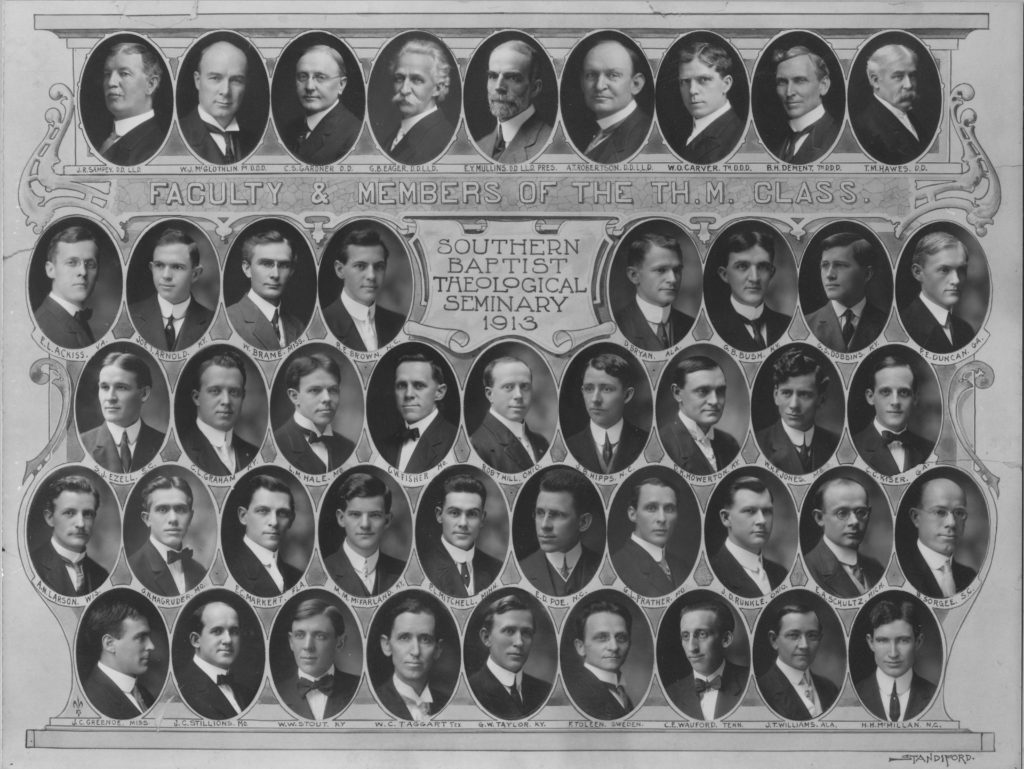

Students with a full slate of classes would have started their Christmas feast with a helping of Hebrew, courtesy of William McGlothlin (beginning) or John R. Sampey (advanced), followed by New Testament with A.T. Robertson or missions with William O. Carver. At 10:30, during the usual chapel time, the campus was undoubtedly nourished with a special time of worship and celebration. A four-course meal followed: church history with McGlothlin, homiletics with Charles Spurgeon Gardner or biblical introduction with George Eager, Sunday school pedagogy with Byron DeMent, capped by a special treat of systematic theology with president E.Y. Mullins, working through chapters six through nine of James P. Boyce’s Abstract of Systematic Theology (Kerfoot revision, 1899).4

Gaines Dobbins, who had graduated with his master of theology degree in May of 1913, was hard at work on his doctor of theology dissertation, Southern Baptist Journalism. He may have spent some of his Yule time reading and writing in the Memorial Library at Fifth & Broadway. He graduated the following May, then served as editor of the SBC’s Home and Foreign Fields periodical before returning to Southern Seminary in 1920 to teach church efficiency and Sunday school pedagogy. Dobbins helped to manage the seminary’s debt during the Great Depression, served as interim president, 1950-51, retired in 1956, then returned at the age of 90 to give lectures at Boyce College in 1975-76. He is credited with pioneering the study of church growth in the SBC.5

Unfortunately, some of the mystery of Christmas was lost on the seminary’s more progressive professors; Carver was chief among them. In 1913, American novelistWinston Churchill published Inside of the Cup, a criticism of church corruption drawing its name from Matthew 23:25, “Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you clean the outside of the cup and the plate, but inside they are full of greed and self-indulgence.” Among other ideas, the book had a particular obsession with refuting the virgin birth.

Carver penned a response in which he at first condemned Churchill’s “violent opposition,” but then conceded, “As a dogma I would, perhaps, care no more for the virgin birth than would Mr. Churchill. As an explanation and a proof of the divinity of the Lord it is both insufficient and needless.” Carver doubted the veracity of the biblical accounts, explaining that they were probably “wrought into the text” at a later time. Carver nonetheless insisted on his belief in the virgin birth, if only as a matter of inspired historical tradition.6

A more lasting and significant legacy of that winter came via the work of A.T. Robertson, who was putting the meticulous final touches on his widely influential, Grammar of the Greek New Testament (1914). His manuscript measured three feet tall. The enormity and complexity of the task drove Robertson’s publisher to insist that he pay for the typesetting, a huge sum that nearly drove him to bankruptcy, until George Norton and E.Y. Mullins stepped in to create a publishing endowment on his behalf.7 The seminary recently recognized Robertson’s 150th birthday (Nov. 6) and his contribution to the study of Greek, a blessed fruit borne out of the studious Christmas of 1913.

Endnotes

1 Seminary Catalog, 1912-1913.

2 Southern Seminary Magazine, January 1893.

3 Greg Wills, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1859-2009, p. 302.

4 Seminary Catalog, 1913-1914.

6 Review & Expositor, April 1914, pp. 290-295.

7 Wills, 268-270.