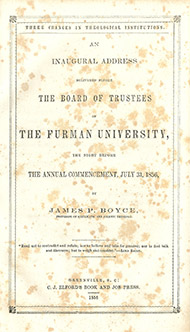

Three core markers of Southern Seminary’s identity are rooted in an 1856 address delivered by James Petigru Boyce titled “Three Changes in Theological Institutions.” This address, delivered upon the occasion of Boyce having joined the faculty of Furman University, offered the following vision statements for what a great Baptist seminary ought to be. The institution must: (1) instruct an abundance of aspiring ministers for the benefit of Baptist churches; (2) produce scholars capable of speaking to the needs of the Baptist denomination and to the common cause of Christianity; and (3) adopt a declaration of doctrine to be required of all its professors. SBTS emeritus professor Thomas J. Nettles summarized them as “the need for an abundant ministry, a learned teaching ministry, and an orthodox ministry.”1

The occasion of the 125th anniversary of the seminary’s doctoral program gives special opportunity to reflect upon the importance of Boyce’s second change, namely, that a Baptist seminary ought to produce excellent scholars to serve both its own denomination and the cause of Christianity in general. Even before the implementation of the seminary’s doctoral program, it had proven itself well adept at training men for both church ministry and scholarship. The most outstanding student to graduate from the seminary in its earliest years was Crawford H. Toy, who soon joined the faculty as an Old Testament professor but ultimately became the first test of the institution’s Abstract of Principles, the culmination of the faculty doctrinal statement insisted upon by Boyce’s third change. Although Toy’s scholarly acumen and other talents distinguished him, his departure from an orthodox view of the Bible’s inspiration necessitated his resignation from the faculty in 1879.

Toy was a notable name among the great scholars who passed through the seminary in its fledging years, and a great number of them proved themselves as the capable Baptist scholars that Boyce envisioned. After the deaths of Boyce and Broadus, every successive president of Southern Seminary has been one of the institution’s own alumni. Furthermore, since the election of Duke K. McCall in 1951, each SBTS president has also been an alumnus of the institution’s doctoral program.

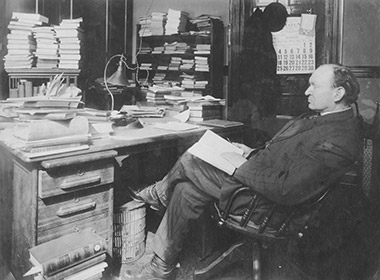

However, the alumnus who became arguably Southern’s most famous scholar, Archibald T. Robertson, never held the office of president. As a student, Robertson quickly distinguished himself as a prodigy with great work ethic in the biblical languages. His particular specialty was biblical Greek, and he joined the seminary faculty in 1888 as an assistant professor to John A. Broadus in Greek and Homiletics.

Robertson’s academic career was marked by high personal character, commitment to orthodox doctrine, and an evangelistic fervor that contributed to the seminary’s high reputation among local Baptist churches. His most significant academic publication was his Grammar of the Greek New Testament in 1914, a 1300-page magnum opus that set a new standard for the study of Biblical Greek in the 20th century and brought greater respect to Southern Seminary.2 Robertson persevered on the faculty as the preeminent authority on New Testament Greek for 46 years, dying unexpectedly on account of a stroke suffered shortly after lecturing his Greek class on September 24, 1934.

the seminary’s former downtown Louisville campus in March, 1912.

Southern Seminary has been blessed not only to train great Baptist scholars but also great Baptist preachers. Among the many alumni who earned widespread reputation for their pulpit abilities, two notable graduates are W. A. Criswell and Herschel H. Hobbs. Contemporaries for much of their seminary education, Criswell and Hobbs earned their doctorate degrees in 1937 and 1938, respectively.

Criswell’s concentration was in New Testament, with a dissertation titled “The Relation of the John the Baptist Movement to the Christian Movement,” in which he noted his appreciation for A. T. Robertson’s Chronological New Testament and other works.3 Criswell became pastor of the bustling First Baptist Dallas. Among all his sermons, his “Whether We Live or Die” address before the 1985 Southern Baptist Pastors’ Conference stands out as particularly memorable and influential. Delivered in the midst of the Southern Baptist Conservative Resurgence, Criswell warned that liberal views of biblical inspiration would lead to the spiritual ruin of every Christian, institution, and denomination that refused to hold faithfully to the inerrancy of Scripture.

Hobbs also focused in New Testament studies, writing his dissertation on the Gospel of John’s relationship to the Synoptic Gospels. He became nationally known as the pastor of First Baptist Church in Oklahoma City, and through his weekly radio broadcasts of “The Baptist Hour,” Hobbs earned the nickname “Mr. Southern Baptist.” Elected president of the Southern Baptist Convention in 1961 and 1962, Hobbs chaired the committee that significantly revised the Baptist Faith and Message in 1963. Criswell and Hobbs were among the last generation of students to be taught by Southern’s historic luminaries like A. T. Robertson, W. O. Carver, and John R. Sampey. In his autobiography, Hobbs recalled Robertson’s explanation for why he was so strict in the instruction of his students: “They are going to be preaching the New Testament the rest of their lives. And I want them to know it!”4

At the May 2017 commencement, the 125th anniversary of the doctoral program, Southern Seminary surpassed the milestone mark of 2,000 graduates.7 More than 400 dissertations and theses completed at Southern over the past two decades are freely accessible online through the Boyce Digital Library, with new additions each semester. Southern Seminary has an unusual heritage of faithfulness and bold innovation, and it continues to be a leader in Christian education with a distinctive focus on serving the churches that entrust its students to train for gospel ministry.

———

Adam Garland Winters is the head archivist for Southern Seminary’s James P. Boyce Centennial Library.

Endnotes

1 Thomas J. Nettles, James Petigru Boyce: A Southern Baptist Statesman (P&R Publishing, 2009), 124.

2 Everett Gill, A. T. Robertson: A Biography (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1943), 175.

3 Wallie Amos Criswell, Jr., “The John the Baptist Movement In Its Relation to the Christian Movement” (Ph.D. diss, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1937), v.

4 Herschel H. Hobbs, My Faith and Message: An Autobiography (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1993), 67.

5 Duke K. McCall, “1973-74 Annual Report,” The Tie, December 1974, p. 6.

6 “Doctoral Program Celebrates 100 Years,” The Tie, Spring 1994, p. 23.

7 Andrew J. W. Smith, “Mohler to SBTS graduates: Celebrate divine calling as God’s messengers,” Southern News, 19 May 2017 [on-line], accessed 14 August 2017, http://news.sbts.edu/2017/05/19/mohler-sbts-graduates-celebrate-divine-calling-gods-messengers/