Redefining Humanity: Evaluating the Metaphysical Concerns of Transhumanist Ideals

Consider for a moment, as Plato once did, a man in a cave, chained to the dusty ground with nothing but the stone wall before him. The inside of the cave is dark, aside from the fire burning in the background with flames creating just enough light to make out the faces of four men chained on either side of him. They are his only company, apart from the ominous figures lurking by that burning fire. Eerie as those figures may seem, they provide his only insight into the outside world, casting shadows of various objects onto the wall before him. Yet, they never satiate his longings to know—to understand in tremendous depth the world around him and the purpose and meaning he holds in this life. He yearns to grasp the fullest potentiality of humanity and achieve it. With frustration, he begins to speak his concerns to those on either side of him.

Having listened intently to his apprehensions, the man closest to him, on his right, introduces himself as Thomas Aquinas. Holding tightly to the traditional views of later medieval philosophy and Christianity, he reassures the man in his quest to understand being, humanity, and the world around him. However, Aquinas caveats his reassurance by explaining all that can be known is known through empirical observation, apart from reasoned scientific research and alchemy. Aquinas informs him that objects within one’s realm of experience seem to, without exception, follow laws of nature, thus observation alone can reap great benefits. He also speaks in great detail of theology, seeking to convince him that such empirical discovery ought to be a preamble to faith, not merely a compend on philosophy. While the man is comforted in his validation of the longings overwhelming him, he still is not satisfied with Aquinas’ approach. ((Collin Brown, Christianity and Western Thought: A History of Philosophers, Ideas, and Movements, vol. 1, (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2010), 134-135.))

The man on the other side of Aquinas, however, catches his attention during a break in the shadow-show happening on the wall in front of him. His name is Francis Bacon. With increased vigor, and just enough skepticism to make the man wary, Bacon assures him that the human being and the natural world are both legitimate objects, not just of observation, but of scientific methodology and study. He seeks to persuade the man of his concept of a well-rounded individual as highly developed spiritually, culturally, morally, and scientifically. The man nods in agreement, but as Bacon continues to theorize about such scientific research, the man sees the danger of allowing those theories to impart a level of control over nature to substantially improve the lives of all humanity within it. ((Nick Bostrom, “A History of Transhumanist Thought,” Journal of Evolution and Technology 14, no. 1 (April 2005): 2, accessed September 18, 2016, http://jetpress.org/volume14/freitas.html.))

At that moment, the man on his left wakes from his dogmatic slumber, interjecting his ideals in both agreement and advancement of Bacon (knowing now that he is outnumbered in his opinions, Aquinas slumps down and falls silent). This new man takes no time to introduce himself, assuming the others are already aware of his successes, yet they later find that his name is Immanuel Kant. Not even pausing for breath, Kant is hasty to make his opinions of enlightenment known, stating that

Enlightenment is man’s leaving his self-caused immaturity. Immaturity is the incapacity to use one’s own understanding without the guidance of another. Such immaturity is self-caused if its cause is not lack of intelligence, but by lack of determination and courage to use one’s intelligence without being guided by another. The motto of enlightenment is therefore: Sapere aude! Have courage to use your own intelligence! ((Immanuel Kant, The German Library: Philosophical Writings, ed. Ernst Behler, (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 1986).))

The man is enthralled, yet taken aback, by his zealous exclamation, and even though he finds himself wrestling with Kant’s words, he is even more determined in his search for knowledge and understanding of human potential.

The man farthest from him, Charles Darwin, clears his throat as if to gain attention prior to making some grand announcement. As much as the man’s chains allow, he turns and listens. Darwin explains his theory of humanity being comprised of matter similar to that which is in peripheral substances and obeys the same laws of nature and of physics. For him, this allows for the capacity to learn to manipulate human nature in many of the same ways that one can manipulate external objects. Darwin continues with his lengthy monologue, and as he does, the man finds himself drifting back into his own mind, caught in questions of whether or not humanity is the endpoint of evolution or only an early phase of it.

The conversation begins to die down, and still lost in his thoughts, the man stares aimlessly at the flickering shadows moving across the wall. Shouts begin to break through the silence, tenacious and unrelenting. The clamor seems to be coming from outside the cave, as if someone were standing at the entryway he was unable to see. In a frenzied hopefulness, the man fights to break his chains, eventually managing to scramble out of them, racing to find the location and source of all the commotion.

Escaping behind the fire, the brightness of the outdoors blinds the man and he quickly crashes into someone just outside the cave. His name is Nick Bostrom, a man, he quickly learns, of advanced education and incredible intellectual vigor. The man is mesmerized, not just at meeting someone such as Bostrom, but at the sheer beauty and expanse of the outdoors that he has been robbed of experiencing for so long. The step he took out of the cave is only the first of many, Bostrom explains to him, and he quickly comes to realize that the possibility of humanity as only one of the earliest stages of evolution is perhaps not too far off. The man listens with eager ears to Bostrom’s evolutionary ideas of transhumanist thought, so carefully built on the theories of those to whom he had previously spoken. He is intrigued, not only by such a novel concept, but by the possibility of the fullest degree of human potential actualized in this virtually limitless individual, the posthuman. The man only needs a moment to see why Bostrom’s ideals could so easily amass a substantial following.

Not only had the man traded filthy chains for soft grass and exchanged the fire and shadow-show for color and sunlight, but Bostrom offered him a response to all his longings that seemingly no intellectual would ever refuse. Nonetheless, the man’s conscience plagued him as he took time to consider all he had been told. Thus, unrestrained acceptance was more difficult for the man than Bostrom anticipated.

What is Transhumanism?

Much of humanity has been trapped in this cave, while transhumanist values have developed behind the fire at a rapid rate. Some are still chained there. Those that are have yet to see that what began as the ideals of one Oxford professor has expanded to a movement with an substantial following. Rooted in centuries of secular thought, transhumanism directly uses medicine, robotics, and technology to surpass the biological limits mankind is forced to face. ((The scope of this paper has necessitated the oversimplification of the discussion of transhumanist ideals. For a more detailed explanation of these views, consider reading Nick Bostrom’s The Transhumanist FAQ: A General Introduction version 2.1 published by the World Transhumanist Association.)) In its broadest claims, transhumanism purports to be an intentional process designed to eradicate disease, eliminate suffering, improve human intellectual and physical capacities, and expand one’s health-span, allowing man, if he so desired, to achieve immortality. ((Nick Bostrom, “Transhumanist Values,” in Ethical Issues for the Twenty-First Century, edited by Frederick Adams, (Philosophical Documentation Center Press, 2003), 2.)) More importantly for transhumanists, these developments refine one’s emotional experiences and give him an increased sense of well-being. Bostrom aims to achieve autonomous, undiluted happiness and unmatched self-control. “We are in the business of living, and the show must go on. Special moments are out-of-equilibrium experiences in which our puddles are stirred up and splashed about; yet, when normalcy returns, we are usually relieved. We [as humans] are built for mundane functionality, not for lasting bliss.” ((Nick Bostrom, “Letter from Utopia,” Journal of Evolution and Technology 19, no. 1 (September 2008): 67-72, accessed September 18, 2016, http://jetpress.org/v19/bostrom.htm.)) His ideologies are an attempt at creating harmony from the chaos and ecstasy from the commonplace, yet they are inefficacious, because Bostrom’s longing lie outside a realistic scope of human finitude.

However, in order to fully comprehend transhumanist ideals and the effects of them, one must first understand the transhumanist community’s foundational view of humanity. The human race suffers from severe limitations. Transhumanists generally hold that such limits imposed by a human’s biological nature are no less than those imposed on an animal by its own. These include physical, emotional, and cognitive capacities, yielding the net result that one’s potential for character development is substantially restricted to the confines of a finite human life. Aging, and ultimately death, wreak havoc on such a pursuit. Bostrom urges one to consider the cultural greats—individuals such as composer Ludwig van Beethoven and writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Perhaps their character would not have changed despite the longevity of their lives. However, it is possible the addition of centuries would have encouraged their increased growth as both men and artists. ((Bostrom, “Transhumanist Values,” 3.)) According to Bostrom, such development assumes at least the possibility of goodness beyond the sphere of humanity, but in its finite state, mankind is robbed of that opportunity.

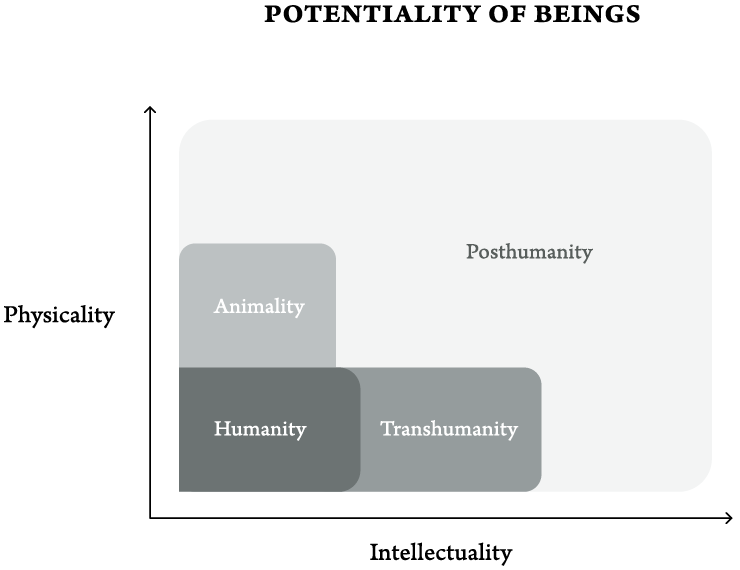

Humanity, in the eyes of the transhumanist is a stepping stone, “a work-in-progress, a half-baked beginning that we can learn to remold in desirable ways.” ((Ibid., 1.)) This fluid definition of humanity assumes, as did the man in the cave, that the current state of humanity is only one of the earliest phases of evolution. Transhumanism, then, stands as the next phase of the evolutionary process. Bostrom traces this line of evolution through the following diagram. ((Ibid., 2.))

Creatures once limited to their animality overcame some limitations as they progressed into the realm of humanity. Through science and technological advancements, one then evolves into a transhuman, an individual functioning in a transitionary phase between the life of a human and a posthuman. The posthuman possesses greater abilities than that of mere human beings, with consistent ability to overcome his biological limitations and maintain a certain level of autonomy. Bostrom illustrates this absence of dependency, observing that

It may then be possible to upload a human mind to a computer, by replicating in silico the detailed computational processes that would normally take place in a particular human brain. Being an upload would have many potential advantages, such as the ability to make back-up copies of oneself (favorably impacting on one’s life expectancy) and the ability to transmit oneself as information at the speed of light. ((Ibid., 4.))

One transforms individually, but the impetus for the evolution of humanity as a whole expresses the need for such transformation.

The thread of enhancement weaves through this entire transformational undertaking. A difficult-to-define term, it bears the general idea of increasing one’s capacity through the improvement of performance, appearance, or other areas of capability whether biomedically, technologically, or otherwise. Currently, medications and surgical procedures limit technological enhancement. However, with the development of increasingly exotic technologies, the push for continued research proves ever more urgent. Fields such as nanotechnology, implantable technology, and cell regeneration are all being pioneered, any one or combination of which could lead to powerful degrees of human augmentation and expansion. ((Ronald Cole-Turner, “Introduction: The Transhumanist Challenge,” in Transhumanism and Transcendence: Chrsitian Hope in an Age of Technological Enhancement, ed. Ronald Cole-Turner, (Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2011), 1.)) The sheer speed of these developments render Bostrom’s ideas both problematic and alarmingly near on the horizon.

Redefining Humanity

Perhaps the greatest of the dangers woven into transhumanist values can be found in its fluid definition of humanity, as it allows for transhumanism simply to be the next step in evolution. Logically, such fluidity implies that humanity has evolved from animal to man through genetic development, and then, through technological enhancement, humanity evolves from man to machine. Humanity within these confines reduces to a mere compilation of easily-manipulated matter. The control of such augmentation lies with each individual which assumes an uncomfortable level of trust society must place on him to make thoughtful and prudent decisions; it assumes that individuals have the freedom to choose not only their outlook on life but also what enhancements are necessary to reach that end. This definition of humanity leaves one wondering how far an individual can be changed before becoming someone or something else—perhaps even a machine. ((Cole-Turner, “Introduction: The Transhumanist Challenge,” 1.))

Not only does this mutability deconstruct the definition of humanity, but it alters the vision of human flourishing as well. Properly understanding what is encompassed in one’s humanity, from a largely evangelical perspective, requires acknowledging that mankind has been created in the imago dei by a relational and triune godhead. God created humanity to live and function on this earth within a biological, non-mechanical body, as observed by scholar Celia Deane-Drummond:

Instead of an exclusive emphasis on the mental powers of willing, choosing, and understanding, human futures need to include more bodily metaphors of gestating, relating, and nurturing. Sexual difference is then included along with other differences, such as that between humanity and other animals, so that it is a difference in degree rather than an absolute one. ((Celia Deane-Drummond, “Taking Leave of the Animal? The Theological and Ethical Implications of Transhuman Projects,” in Transhumanism and Transcendence: Christian Hope in an Age of Technological Enhancement, ed. Ronald Cole-Turner, (Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2011), 123.))

Working toward becoming a posthuman, particularly in its most extreme form of uploads does not necessitate the development of some sort of superhuman; rather humanity becomes a collection of mechanical parts and binary code. In one fell swoop, transhumanists make a direct attempt at abandoning humanity, ignoring God’s deliberate design, and thus forsaking the unique aspects and opportunities for it to flourish as it was originally intended.

In addition to the necessity of a biological, non-mechanical body, to be a human living on this earth requires the possession of a soul. Humanity has depth, an essence housed in such a possession. The soul is the cornerstone of personhood, the key to moving beyond only existing as a creature in the world. In a sense, Kant’s theory of the transcendental apperception applies. One could not be considered a person apart from the presence of a soul, for he would be a simple collection of body parts; nor could one be considered a living human with only a soul not focused to the particular view point of embodiment. ((Robert W. Jenson, Systematic Theology: The Works of God, vol. 2, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 97.))

Due to the influence of dualist philosophers such as Plato and Descartes, the idea of the soul as synonymous to the mind has become commonplace. However, some philosophers like Aquinas fought against the assumed similarities to embrace the idea of the soul as a substantial form—that which informs the matter composing living beings. The soul endows a being with the capacities crucial to and consistent with its life and existence. ((Jason T. Eberl, The Routledge Guidebook to Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae, (New York: Routledge, 2016), 87.)) However, intellective and volitional capacities of the soul are not dependent on bodily organs. The brain is not the “seat of the soul,” for the soul cannot be reduced to neural activity. “While neural happenings occur simultaneously whenever one thinks or wills, the act of thinking or willing is not identical to such neural happenings, and the latter is ontologically dependent on the former.” ((Eberl, The Routledge Guidebook to Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae, 87.)) Aquinas’ hylomorphic ideals reject both those of dualism and materialism by holding to the composite unity of the immaterial soul as it informs a material body. This soul-body relationship understands that an organized, living body can only exist insofar as the soul is informing it. ((Ibid., 85-89.))

Thus, the conclusion recognized mankind as embodied, ensouled, and relational. Deane-Drummond explains this relational identity of humanity well, stating that

An emphasis on treating all creatures as “Thou” instead of “It,” to use Martin Buber’s terminology, changes the ethos of human aspiration from one that is driven by technological achievement to one that is filtered through human goods, worked out in collaboration and in consultation with others. A shift toward relationship is a reminder that life that is received as a gift includes the giftedness of others in relation to human beings. Although not exclusively a Christian concept, the notion of gift and the welcome of the other as other counteracts the more huberistic tendency for control over uncertain features that is woven into transhumanism. ((Deane-Drummond, “Taking Leave of the Animal?” 123.))

Removing relational capacity distorts the image of the Trinity intrinsic to mankind. Individuals live to possess and experience that which has been set on their hearts. The relationship of the three persons of the Godhead values willing service, deeper friendship, appreciation, respect, and love. ((Paul David Tripp, “God’s Wisdom, Your Relationships,” Desiring God, June 1, 2011, accessed November 24, 2016, http://www.desiringgod.org/articles/gods-wisdom-your-relationships.)) This model has been set on the hearts of humanity; this is the model mankind ought to imitate. Depriving people of relational capacity severely damages their capability to do so. A shared human condition produces solidarity. Yet, in a posthuman world of autonomy, humanity loses its communal roots of creaturely being. ((Deane-Drummond, “Taking Leave of the Animal?” 124.)) To enhance man in the way transhumanists desire strips him of all three—non-mechanical body, soul, and relationship—fundamentally robbing him of a life that is fruitful and as it ought to be. Overall, this removal could be considered more of an intentional retrograde, seeking powerful and limitless beings that are controllable, rather than a true advancement of any kind.

Metaphysical Ramifications of a

Transhumanist Definition of Humanity

To function on a fundamentally transhumanist definition of humanity breeds significant danger and produces two substantial metaphysical concerns. The first is an issue of the essence and function of a person. Because the transhumanists’ fluid definition allows for humanity to evolve from man to machine, the essence of an individual progressively diminishes. Through this transition from creature to material, man becomes entirely functional. The essence of an individual, housed in his possession of a soul, maintains his humanity, but loses substance in the transformation. Only functionality can be maintained virtually; the essence of mankind cannot.

Transhumanists have reached so far for the control of an individual and the future he aspires toward that they cease to believe in the possibility of humans as “complex creatures who resist reduction to functional mental units.” ((Ibid., 124.)) Many theologians appeal solely to mystery, and hesitate to discuss in specific detail the likeness of God and humanity, while transhumanists fly to the other extreme, removing any sense of mystery all together. The transhumanist community shows far less concern for knowing the future scenarios of humanity than for understanding future human projections as strictly wedded to technological invention and enhancement. Their attentions lie less with human flourishing than cyber-cultural values and perfectionist concerns.

Transhumanists have also placed the burden of decision on the individual who bears the responsibility of determining the makings of a good life. Aside from the endless debates about what characteristics philosophers deem necessary for a “life well lived,” the autonomous individual is their only option. ((Cole-Turner, “Introduction: The Transhumanist Challenge,” 2.)) Yet, the danger lies in its subjectivity. The lines become blurred between man as human and man as machine, and distinguishing between biological necessity and personal preference of enhancements becomes a near impossibility. Ethical guidelines cannot be effectively established within the scope of their research. ((Certainly Christian theology and philosophy provide guidance for proper limits and it is necessary for those ethical guidelines need to be clearly spelled out. However, doing so reaches far outside the scope of this paper.)) The transhumanists see enhancing one’s life as increasing the goodness within it, but if goodness ought not fall victim to a sliding scale with no standard, leaving those decisions to the conscience of the individual (even the enhanced individual) may be a greater risk than the transhumanist would care to admit.

Transhumanism and the Christian Perspective

Undoubtedly, aspects of the posthuman pursuit can be commended. Every individual searches for goodness and truth. Transhumanists, intellectual individuals who have bravely ventured into uncharted territory on this search, have wrapped their lives around the developing theories. They strive for good, but look in the wrong place, so they attempt to create that which they cannot find.

The Bible offers individuals the ultimate goal of transhumanism. Bostrom describes this aim well, writing that “Human life, at its best, is fantastic. I’m asking you to create something even greater. Life that is truly humane.” ((Bostrom, “Letter from Utopia.”)) Transhumanism can only offer a humane life by removing one’s humanity, while classical Christianity offers people humane life rooted deeply within their humanity and within Christ’s. ((c.f. 2 Corinthians 4:14-16.)) God the Father promises believers resurrected bodies upon Christ’s return, and not only does he faithfully fulfill those promises, but a fully restored life necessitates the resurrection of the individual. Christian philosophers and theologians do not dispute the idea of the resurrection of an identifiably human body.

Thus the hope entertained by the church is not for the mitigation or evasion of death, but for its undoing. The church does not hope for the survival of some part of the human person, not even an “essential” or “central” part, or for a redefinition of death as liberation from the material world. When the Lord raises his people from the dead, he does not rescue them from a neutral if unfortunate circumstance or reach an adjustment with another power; he conquers an enemy. ((Jenson, Systematic Theology, 329.))

The lives of the redeemed will be congruent with and moved by divine life, resurrected and of irreducible personal identity. ((Ibid., 354.))

Conclusion

All of these thoughts and concerns filled his head as the man sat for hours outside the cave considering what he and Bostrom discussed. Physically, he had only taken a few short steps outside the cave, but mentally, he felt he traveled miles without respite. The intellectual journey he experienced satiated his longings to understand deeply for a moment, but he could not understand Bostrom’s enthusiasm for a movement that seemed to hold so little hope. The man stood and began to pace back and forth outside the entrance of the cave as he continued to contemplate everything he learned in past few hours.

After several passes, the man stopped suddenly at the mouth of the cave—something had changed. He still could not see the men to whom he had spoken that morning as they remained chained on the other side of the fire, but he was not concerned for long as the fire itself held his attention. It had transformed. No longer did the flames cast grave misrepresentations of life onto the cave walls. The fire was no longer a symbol of all he had been robbed of truly experiencing. He gazed intently at it, desiring to determine the differences in it. What he saw was different to be sure, and not unfavorably so, but still recognizably human in form and function as if it were truly a resurrected body. The sight was unlike anything he had ever seen and stirred his affections as nothing else ever had. He knew in that moment a far more satisfactory solution than transhumanism existed. A smile spread broadly across his face as the man began to walk away from the cave, assured that in that moment, his longing to truly know had finally been satisfied.